Evan McGlinn

Catch Me If You Can

Sport fishing for marlin and sailfish has become more sophisticated than ever. With satellite boats strategically placed and yachts acting as the motherships, tournaments have turned into scenes from Battlestar Galactica.

BY EVAN MCGLINN

Jessica Haydahl

At dawn, an armada of ships sets out 50 miles or more offshore to catch billfish.

Tall, tanned, and sporting polarized sunglasses, Brooks Smith strides past dozens of multimillion-dollar billfishing boats docked at the packed marina in Los Sueños, Costa Rica. Catchy names like Big Oh, Reel Pushy, Morgasm, and Pelagic Magic are painted in elaborate designs on the transoms of the docked vessels. Soon this place will be empty and all these ships will be trolling the calm, warm waters of the Pacific to compete in one of the most famous billfish tournaments in the world—The Los Sueños Signature Triple Crown.

It’s early, 6:15 a.m., and the sun is just starting to hit the spotless stainless steel and glass of the fleet, giving the marina a magical glow. At the end of the dock, Smith bangs a quick left and steps aboard his 60-foot Bayliss yacht with the name Uno Mas airbrushed across the back. As he sits down in the sleek, teak stateroom (accessed through a push-button, air-powered sliding door), his crack team of deck hands have already released the lines. Uno Mas eases out of her slip, one step in an almost automatic routine Smith performs more than 100 days a year.

Smith checks the large flat-screen TV in the cabin on the ship’s starboard side. In bright colors, it shows detailed satellite images of the Costa Rican coast complete with current movements, plankton, and water temperatures. He and his team of anglers, friends from Savannah and Cape May whom he has known for years, discuss their game plan. They decide to venture out 50 miles from the coast—the farthest allowed under tournament rules—where they believe conditions look right for hooking into sailfish and hopefully, a prized blue marlin.

Evan McGlinn

A sailfish jumps off the starboard bow of the Uno Mas, which caught over 12 billfish in one day during a practice round.

Evan McGlinn

Costing about $1,000 each, large billfish rods need to carry hundreds of yards of line.

Fishing at this level does not come cheap and the sport has changed quite a bit since the days of Ernest Hemingway and Zane Grey. Back in the 1920s and ’30s, macho men caught billfish in small boats, sometimes landing huge fish using just a handheld line and fishing their baits hundreds of feet deep.

Today, the sport is as macho as ever (though there are many tournaments with a female division as well), but it’s less about muscles and more about the size of your bank balance. Last year, a 510-pound black marlin on the final day of the Cabo San Lucas Bisbee’s Black and Blue Billfish Tournament was worth a whopping $3 million. But that’s just a drop in the bucket.

Elite billfish anglers like Smith and his competitors spend millions of dollars to build bigger, faster boats and outfit them with high-tech gizmos like the full-circle color sonar Furuno CSH-8L Mark-2 (furuno.com).

The $80,000 unit can cost tens of thousands to install, but it’s deadly accurate and can spot a fish within 800 feet of the boat, as well as small baitfish that marlin and sailfish dine on. “The radar is so advanced,” says Marlin magazine Editor-in-Chief Sam White, “that a captain can spot one or two birds feeding on fish 8 to 10 miles away.”

There are advantageous ways to spend money off the boat too. From a small office in West Melbourne, Florida, a company called ROFFS (roffs.com) provides custom NOAA and NASA satellite analysis starting at $60. The analysis provides and explains to the anglers the best spots to fish on any given day. “It is a big ocean, and you don’t want to waste your time, fuel, and money searching for fish and guessing where the best conditions are,” says ROFFS President Matt Upton, who processes over 19,000 requests a year and has helped set six International Game Fish Association (IGFA) world records, two United States records, one Bahamas record, one Gulf of Mexico record, and 27 state records. Upton’s team of five fisheries and satellite oceanographers looks at a variety of factors, including sea surface temperatures, bottom structure, weed lines, water mass boundaries, and ocean color chlorophyll indicators to get a precise picture of where the fish will be.

“Greener water is an indicator of more plankton and surface life,” says Upton. “Bluer water indicates less plankton and clearer water, but certain fish like different waters. For instance, most marlin like clear, blue water, while other species thrive just as well in greener water.”

Evan McGlinn

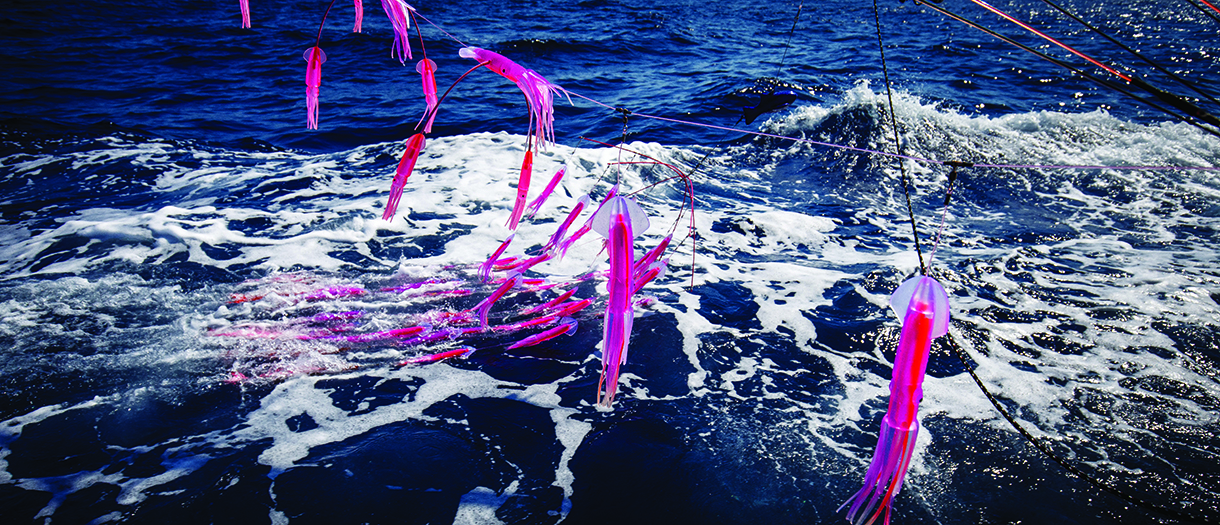

Colorful teasers on the port and starboard side attract the billfish to the surface.

While technology has advanced above water, down below, Smith’s prey has stayed the same for millions of years. When man wasn’t even standing upright, billfish hunted the earth’s waters. The great blue marlin (the world all-tackle record off Kona, Hawaii, stands at 1,376 pounds) cruise the surface at around 1 to 3 knots, preferring water temperature in the range of 75 to 81 degrees—the sort of water found in Los Sueños.

Blue marlin can dive more than 2,000 feet down to stuff themselves on squid before rocketing back to the surface. Known to swim extraordinary distances, a marlin tagged near Puerto Rico popped up 120 days later offshore of Angola, Africa, 4,776 miles away.

Immortalized by authors such as Hemingway and Tennessee Williams, they have long captured the imagination of fishermen appreciating what these fish can do and what it takes to capture one. Writes author Philip Caputo in “The Ahab Complex,” published in The Key West Reader, the marlin “can defend themselves against anything that swims,” adding that their only natural enemy, the mako shark, loses a fight most of the time and that “a marlin’s bill has pierced 22 inches of solid wood.”

To pursue such a prize, the human enemy goes to great lengths, and with better success than the mako. A suitable billfish boat is essential, and no other craft in this elite group of sport fishermen is more widely known for pushing the tech envelope than Jaruco—a 90-foot Jarrett Bay Boatworks (jarrettbay.com) model owned by angler Ralph de la Torre. The Boston-based CEO of Steward Health Care Systems LLC named it after the town where his parents were born in Cuba. “It’s probably the most advanced sport fishing boat in the world,” says Randy Ramsey, president of Jarrett Bay. “The engineering of the boat alone costs $5 million. It was a challenging process.”

Three years in the making, almost everything on Jaruco, including the stringers, the bulkhead, and the water and fuel tanks are made of carbon fiber. Even Jaruco’s six toilets are carbon fiber. “If you have ever worked on one around your house, you know that porcelain is pretty darn heavy,” laughs Ramsey, whose company is based in Beaufort, North Carolina. Stainless steel is the standard material on other boats for the shaft that runs from the engine to the propeller. On Jaruco, a drive shaft made of titanium saves 1,700 pounds in weight. The end result is a boat that is nimbler and weighs 40,000 pounds less than a typical 90-footer. Jaruco can cruise at 45 knots—as fast as a 65-footer, says Ramsey.

For Ramsey, the technological innovations are thrilling and “we incorporate a lot of those innovations into the new boats that we are building.”Smith, who favors custom boat designs, currently owns three sport fishing boats—all called Uno Mas. He has his 60-foot Bayliss based full time in Costa Rica and he owns another 68-foot Bayliss and a 77-foot Willis. Having multiple boats makes it a lot easier to fish competitively around the world and ensures that “we don’t have to move a boat thousands of miles in just a few days,” says Smith. “It’s also less wear and tear on the boats.”

In Los Sueños, Smith taunts marlin at the surface by pulling blue and pink rubber squid behind the boat to entice the fish to bite. Four to five anglers are in the back of the boat armed with reels carrying over 600 yards of braid backing and 25-pound test monofilament connected to modern Alutecnos reels costing upward of $1,000 each. The anglers fish with dead ballyhoo (rigged to swim naturally as if alive), which the marlin and sailfish love to nibble on. When a billfish bites, the anglers must have a subtle touch to hook them. Captains only fish with anglers who have mastered the art of these techniques in order to win tournaments.

Over the course of the tournament, Smith never touched a rod. He navigated his 60-foot Bayliss armed with an old-fashioned, handheld counter like an usher at a movie theater. He would click it every bite whether the fish was caught or missed. Smith assures that you don’t really need any of the bells and whistles to be successful in billfishing. In the end, he says, “you don’t have to be a pro to be successful. It’s not like golf.” After three days of fishing, the crew of Uno Mas won Leg 3 of the Los Sueños Signature Triple Crown with 40 sailfish (100 points each) and two blue marlin (500 points each). All fish were released back into the Pacific. And the team banked $70,000 in& prize money.

Courtesy One&OnlyPalmilla/Cool Baja

An elite billfishing boat will carry dozens of rods and reels.

Courtesy Los Sueños Resort and Marina

Brooks Smith’s Uno Mas is one of three boats he owns for sport fishing tournaments.