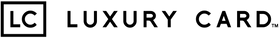

Early Sunday Morning, 1930, oil on canvas, 35 3/16” x 60” Digital image © Whitney Museum of American Art / Licensed by Scala / Art Resource, NY

An American Life

One of the most celebrated artists of the 20th century, EDWARD HOPPER painted melancholic cityscapes and rural scenes imbued with loneliness and uncertainty—now eerily prescient.

Hopper’s life (1882–1967) spanned World War I, the Roaring Twenties, the Great Depression, and the Jazz Age. It continued through the rise of Hollywood, World War II, the nuclear age, and the Cold War, culminating amid the Vietnam War, the birth of rock and roll, and the counterculture of the 1960s. Yet, throughout this dynamic epoch, his work remained divorced from the grand history of headlines and celebrities.

His choice of subjects seems almost calculated to short-circuit success. Nearly all of his pictures depict everyday places and unextraordinary people doing nothing in particular. His cityscapes and landscapes are neither awe-inspiring nor picturesque, and their occasional inhabitants tend to be bored cyphers rather than dynamic individuals. As physical objects, the canvases are as modest as their subject matter. Never monumental in scale, often subdued in tone, they are painted in a sort of bland, straightforward manner, devoid of overt virtuosity. And yet, these works are hailed as artistic landmarks and quintessential documents of American life.

Hopper completed 366 oil paintings, hundreds of watercolors, about 70 etchings, and numerous preparatory drawings and illustrations. Most of his paintings are in American museums, though major works belong to Bill Gates, Steven Spielberg, Barbra Streisand, and Steve Martin. One of his paintings, Chop Suey (1929), depicting two women in a Chinese restaurant, sold in 2018 for $92 million, the record for his work at auction.

Consider the psychological dimensions of America, and the appeal of Hopper’s work deepens. He is known as the painter of loneliness, representing the somber life of individuals absorbed in their own worlds. Even his unpopulated scenes are enshrouded in an enigmatic stillness, as if time has paused to allow us to contemplate the peculiar sadness of its passing. Emotive power is what Hopper so expertly commands.

“My aim in painting has always been the most exact transcription possible of my most intimate impressions of nature,” he once explained. He believed that realism was necessary to reflect an artist’s emotional encounter with the world. Toward the end of his life, he complained that “the loneliness thing is overdone,” but he acknowledged, “It’s probably a reflection of my own, if I may say, loneliness. I don’t know. It could be the whole human condition.”

South Carolina Morning, 1955, oil on canvas, 30 3/8” x 40 1/4” Digital image © Whitney Museum of American Art / Licensed by Scala / Art Resource, NY

IN THE BEGINNING

Hopper worked for decades before gaining recognition. He was born in 1882, the second child in a middle-class Baptist family in Nyack, New York, a town on the Hudson River 25 miles north of Manhattan. The wood-frame house where he grew up, a few blocks from the river, is today a historic landmark and art center. His father had a dry goods store and his mother was an amateur artist. A gawky 6-foot-tall adolescent, Hopper spent much of his time on his own, exploring the docks, making model boats, and drawing and painting. His parents encouraged his art, but insisted that he get practical training.

He studied commercial illustration at a school in Manhattan, then enrolled at the New York School of Art, a forerunner of Parsons, whose founder, American impressionist William Merritt Chase, had broken from the academic Art Students League to advocate more progressive approaches. Another teacher, Robert Henri, admired Frans Hals and Édouard Manet, and urged students to paint modern life. Hopper excelled and after graduation stayed on to teach, then from 1906 to 1910 made three trips to Europe, spending most of his time in Paris. Picasso, Braque, Matisse, and others were rising stars, but Hopper had no contact with the avant-garde. He studied the masters in the museums and painted like a late impressionist. His most important work from this period, Soir Bleu (1914), is a café scene in the French tradition, with a motley cast of characters that would be right at home in a Toulouse-Lautrec.

He eked out a living illustrating trade and business journals, but he loathed the work and struggled to support himself. A sailboat picture that he submitted to the landmark Armory Show of 1913 found a buyer, but it was the last painting he would sell for a decade. He moved from Midtown to a walk-up on Washington Square North in Greenwich Village. The flat had no toilet and was heated by coal that he lugged up the stairs, but Hopper would remain there for the rest of his life. (The apartment, now owned by New York University, can be visited by appointment.)

Unable to sell oil paintings, in 1915 he began making etchings influenced by Rembrandt, Degas, and John Sloan—melancholic scenes of the city at night, women in working-class bedrooms, and lonesome rural houses. Prints like American Landscape (1920), which depicts cattle crossing a railroad track near a farmhouse, contain all the elements of Hopper’s mature work. The Whitney Studio Club, led by patron Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, who later founded the Whitney Museum of American Art, mounted his first solo show in 1920—organized by his friend and former classmate Guy Péne du Bois—but none of the 16 paintings sold.

In 1923, on a painting trip to Gloucester, Massachusetts, he began courting Josephine Nivison, an artist who had attended the New York School of Art. She helped place his watercolors in an exhibit at the Brooklyn Museum, and the museum purchased his portrait of a sun-drenched Gloucester house, The Mansard Roof (1923). (The house is one of many extant sites that Hopper biographer Gail Levin photographed for her book Hopper’s Places.) They married the following year, when they were both in their early 40s, and Jo moved into the Greenwich Village walk-up.

Gas, 1940, oil on canvas, 26 1/4” x 40 1/4” “Edward Hopper” at the Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel 2020. © Heirs of Josephine Hopper / 2019, ProLitteris, Zurich / Artists Rights Society (ARS); Photo: Mark Niedermann

THE MIDDLE

Petite and chatty, a former actress and school teacher, Jo was the opposite of her 6-foot-5-inch taciturn husband. “Sometimes talking with Eddie is just like dropping a stone in a well,” she said, “except that it doesn’t thump when it hits bottom.” Though she admired his art, their 43-year marriage was marked by mutual resentment and rancor. She served as his model, secretary, and manager, and let her own artistic career fade under his condescending gaze. We know from her diaries that she was a virgin when they met, and she gained no pleasure from their lovemaking. “The whole thing was entirely for him, for his benefit,” she wrote. She described brawls in which he slapped and pushed her around, and she scratched and bit, even drawing blood. On their 25th anniversary she quipped that they “deserve a medal for distinguished combat,” and Hopper duly sketched her a coat of arms featuring a rolling pin and ladle.

But their partnership kindled his success. He soon had his first solo show at a gallery, Frank K.M. Rehn on Fifth Avenue, whose owner represented major American artists and would remain Hopper’s dealer for the rest of his career. The show sold out, and Hopper quit illustration to focus on his own work. He and Jo bought their first car and began taking road trips to New England, the Southeast, and the West Coast, and in later decades they often visited Mexico by rail. They summered in South Truro on Cape Cod, and in 1934, with an inheritance she had received, the couple built a house and studio on land they had acquired on a bluff overlooking the ocean. Hills, South Truro (1930), completed during that first visit to the Cape, depicts the landscape where they eventually decided to make their home.

The composition proceeds from a secluded house in the foreground, past a railroad track, into a middle ground of softly undulating hills carpeted in fecund green and umber in alternating light and dark. In the distance lies a ribbon of blue sea beneath a sky veiled with delicate pale-yellow clouds tinged with eastern sunlight. He makes such scenes memorable by stripping away unnecessary detail, creating strong effects of light and shadow, and using a limited palette brushed on in broad flat areas of color. The characteristic feelings of quiet and solitude are present, but so is a subdued optimism, perhaps evidence of a fondness for the place that led him to return nearly every summer.

By this time, Hopper’s career was in full swing. House by the Railroad (1925) had become the first oil painting to enter the permanent collection of the newly opened Museum of Modern Art. The Whitney purchased Early Sunday Morning (1930) and hung it in their inaugural show in 1931, and the Metropolitan Museum bought the restaurant scene Tables for Ladies (1930). His work appeared regularly in the Whitney’s annual and biennial shows, and in the American Pavilion at the Venice Biennale. MoMA mounted a retrospective in 1933, the Art Institute of Chicago surveyed his watercolors in 1939, and the Whitney held a retrospective in 1950—curated by Hopper’s ardent supporter Lloyd Goodrich—that traveled to Boston and Detroit.

Working mainly in New York City and small towns along the New England coast, he depicted unextraordinary and overlooked people and places. Ignoring the grand Art Deco skyscrapers that defined progress and modernity, he trained his eye on aging apartment buildings, empty parks, darkened theaters, office interiors, and hotel lobbies. He never painted traffic jams or airports, bustling factories or markets, packed speakeasies, or baseball games. He had no interest in world leaders, pop-music icons, or hippies. The teeming throngs are absent; present are solitary figures in sparsely furnished rooms, with just a window hinting at the siren call of public life.

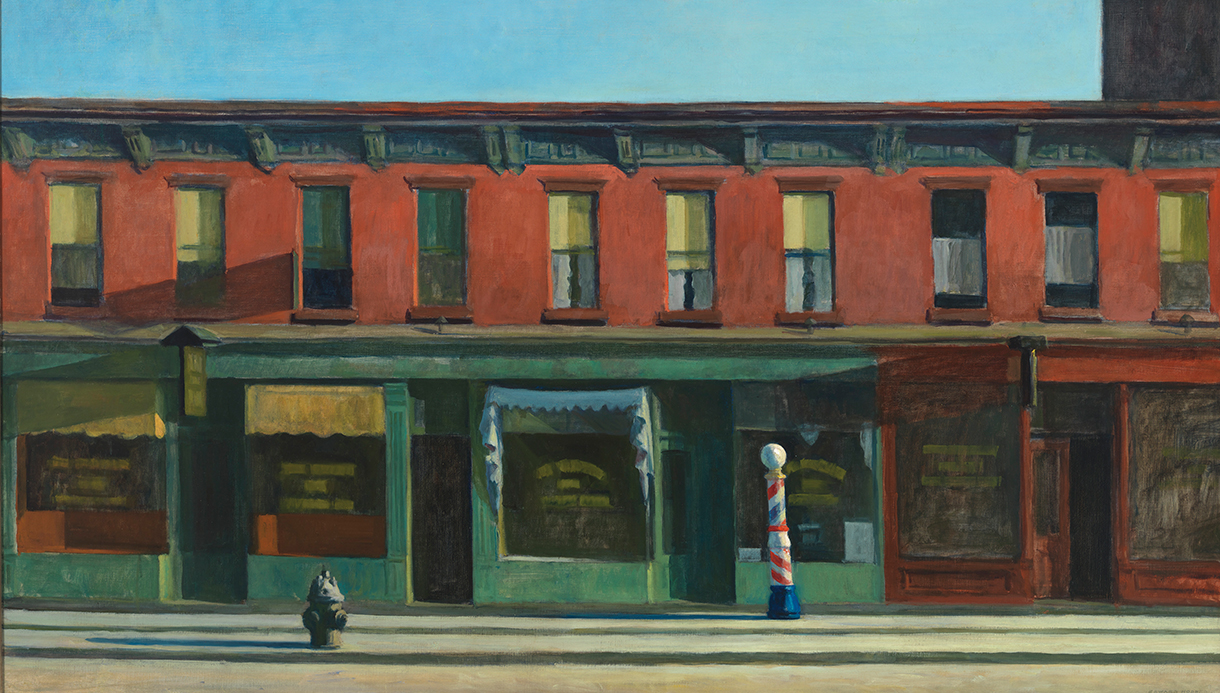

Hopper was especially fascinated with women and their changing roles in society. He painted some home alone, sewing, reading, or smoking, sometimes nude and often looking out the window. When they are joined by their husbands, there is an atmosphere of alienation and repressed sexuality. He portrayed women moving out into the world: an office girl drinking coffee at the automat, a movie theater usherette lost in thought, a waitress arranging the display in a restaurant window, and a red-headed striptease artist shimmying across the stage in his raciest picture, The Girlie Show (1941).

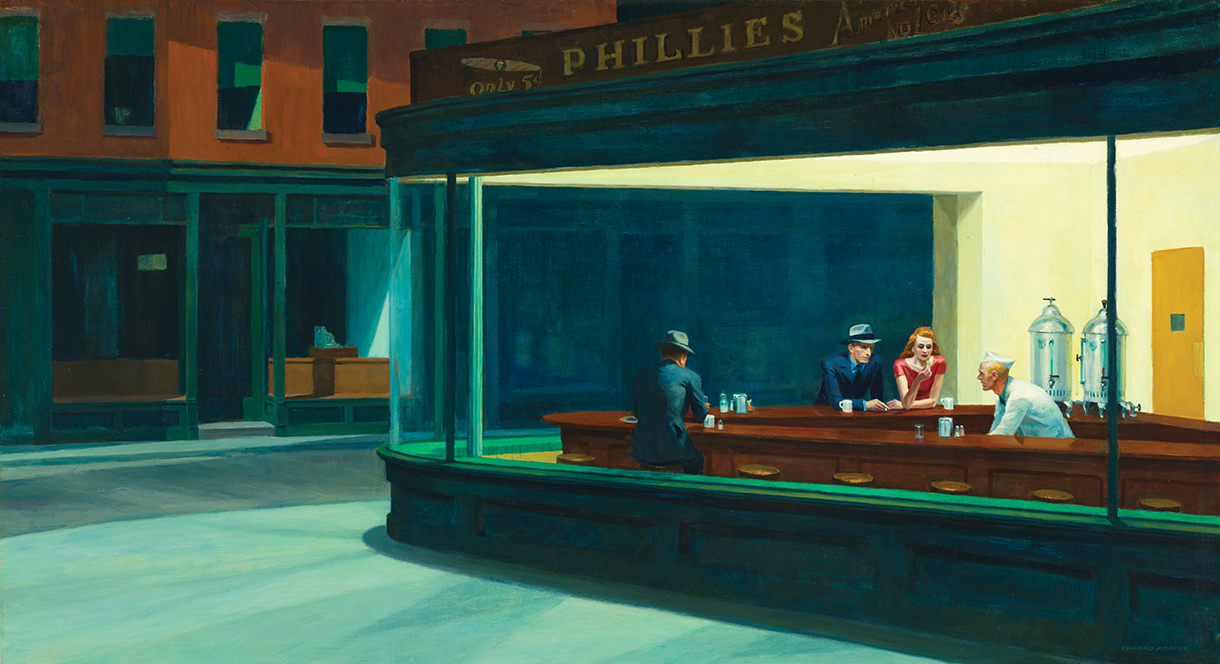

The following year Hopper painted his most recognizable masterpiece, Nighthawks (1942)—a nocturnal diner scene that has become as iconic to Americana as Grant Wood’s pitchfork-wielding Midwestern couple in American Gothic (1930). (Both works are at The Art Institute of Chicago.) The subject is nothing special. Two men are in dark suits and gray fedoras, one of them sitting at the counter next to a woman with a red dress and chestnut hair. A white-clad server looks up at the couple while continuing his work. We view the scene as if passing by at night, looking through the restaurant’s plate-glass window that wraps the corner of the café. The bright light of the interior floods the foreground sidewalk and angles across a dark, narrow street.

Hotel Room, 1931, oil on canvas, 60” x 65 1/4” Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza / Scala / Art Resource, NY.

Automat, 1927, oil on canvas, 28” x 36” © DeA Picture Library / Art Resource, NY.

AND THE END

Hopper was not religious, but he was conservative, a lifelong Republican who voted against Franklin Roosevelt. He opposed the New Deal’s employment of artists in the Works Progress Administration because he felt it promoted mediocrity. He never dabbled in abstraction, expressionism, or any of the other -isms, but he shared the modernist search for visual means to convey subjective experience. He joined the “Reality” group that protested museums’ favoritism for abstraction, and in 1953 wrote in the organization’s journal, “The inner life of a human being is a vast and varied realm and does not concern itself alone with stimulating arrangements of color, form, and design … Painting will have to deal more fully and less obliquely with life and nature’s phenomena before it can again become great.”

Like many American artists, he was determined to develop a native art distinct from European influence. In the catalog of his 1933 show at MoMA, Hopper wrote that after decades of “domination” by France, it was high time for American artists to move on from their “apprenticeship.” He distinguished himself from the so-called Ashcan School painters, including John Sloan and George Bellows, whom he knew. They illustrated vignettes of American life, but Hopper said that they captured America and he was more interested in capturing himself. Their realist successors were the American Scene painters, Thomas Hart Benton and Grant Wood, but Hopper deemed their pictures caricature.

In his own work, he portrayed American life refracted through the lens of his own personality. The artist Charles Burchfield saw him as the truest exponent of American realism. In Hopper, he wrote, “we have regained the sturdy American independence which Thomas Eakins gave us, but which for a time was lost.”

We think of Hopper as a prewar artist, before Abstract Expressionism and Pop Art, but his final decades overlapped with Mark Rothko, Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, and Andy Warhol. As the art world moved on, so did the critics, but he remained a respected eminence, profiled in Time magazine’s 1956 Christmas issue in a cover story titled, “The Silent Witness.”

His later works take on an abstract grandeur and metaphysical gravitas. Rooms by the Sea (1951), an interior with a door that appears to open directly over the sea, has the enigmatic quality of a Magritte. Streaming sunlight creates a hard-edged geometry on the wall, an element that takes center stage in an even more minimal work, Sun in an Empty Room (1963). In this summa, Hopper jettisons everything but the bare essentials of his art—light and shade, surface and volume, and the interpenetrability of interior and exterior space.

He did not entirely abandon the anecdotal in his late years. Western Motel (1957) is an almost tender recollection of travels with Jo. A blond woman faces us from the foot of a bed, and suitcases rest on the floor as if she and her traveling companion have just arrived or are about to leave. Through the huge window behind her we see the hood of their green car, a ribbon of road, and sun-topped hills beneath the open sky. In his final painting, Two Comedians (1966), a pantomime couple dressed in white, stand-ins for Ed and Jo, take the stage one last time for their final bow.

Hopper’s health had long been in decline. He had thyroid and pituitary problems—possibly a cause of his depression—and in 1948 a prostate operation led to the first of many hospitalizations. In 1967, at 84 years of age, he died in the Washington Square studio. Jo passed away 10 months later.

He and his fictive cast of characters, familiar and accessible, serve as mirrors in which citizens recognize themselves in a dimmed version of the American Dream, one that chimes with Henry David Thoreau’s observation that “the mass of men lead lives of quiet desperation.” Amid the COVID-19 pandemic, Hopper’s somber vision has gained renewed currency, with his paintings posted on social media as evocations of deserted cities and lonely people sheltering at home. They remind us of having felt alone and withdrawn from society, and that these moods are not unique. This therapeutic function, coupled with his image as an American original, account for Hopper’s canonical stature and enduring popularity among connoisseurs and the general public.

Nighthawks, 1942, oil on canvas, 33 1/8” x 60” The Art Institute of Chicago / Art Resource, NY

A LEGACY THAT LIVES

The largest cache of Hopper paintings was given in the bequest from Jo to the Whitney Museum. The gift includes not only masses of art but ledger books in which Hopper made thumbnail drawings of every oil, watercolor, or print that he planned to sell. Jo penciled in the dates, descriptions, sale prices, buyer names, notes on exhibitions and reviews, and notes about where and how the works were made, even the brands of paints and canvas used.

The Whitney frequently mounts Hopper retrospectives, and whenever they do attendance surpasses everything else on view. Scholars and curators continue to explore aspects of his work. Last winter, the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts presented Edward Hopper and the American Hotel, a show that will be at the Indianapolis Museum of Art through September. And his reputation in Europe has grown steadily in recent decades. On view at the Beyeler Foundation near Basel, Switzerland, until July 26, is Edward Hopper: A Fresh Look at Landscape.

German filmmaker Wim Wenders created a Hopperesque short to accompany the Beyeler show, joining Hitchcock, Ridley Scott, and other film directors who pay homage to Hopper’s film noir aesthetic. Photographers Robert Adams, Diane Arbus, Lee Friedlander, and William Eggleston share Hopper’s penchant for solitary figures in humble settings brimming with psychological tension.

The British writer Geoff Dyer suggests that Hopper “could claim to be the most influential American photographer of the 20th century—even though he didn’t take any photographs.” Hopper resonates also with writers and musicians. Joyce Carol Oates wrote a poem that gives voice to the characters in Nighthawks, Tom Waits composed the song “Nighthawks at the Diner,” and Madonna titled her 1993 tour The Girlie Show after the Hopper burlesque painting of that name.