Atlantic Ocean, August 01, 2016, early morning.

Color Her World

Photographer ANDREA HAMILTON captures a certain magic in her photos, one that she’s painstakingly unearthed via a careful, methodical process. Her current focus? A groundbreaking digital platform.

Atlantic Ocean, July 10, 2018, late evening.

“Companies will spend millions of dollars to put a hole in the ground and they won’t [return] with anything,” says visual artist Andrea Hamilton. “But then there are these four or five people in the world who can marry everything. They look at the science but then look at the earth and through their connection with it, have this sixth sense. They know where the silver vein is.”

In the years before conceptual art became Hamilton’s central channel, she worked as a mining analyst traveling the remote expanses of Chile, Peru, Argentina, and Brazil. She wrote reports about each place, and on her own time, she says, “I took all the photos I wanted.” But much like the geologists engaged in a process of excavation, Hamilton, who is 53, with long blond hair and storm-blue eyes, began to probe the metaphysical depths of water.

She has spent more than two decades photographing the ocean, which she describes as “a mirror to the vastness we carry inside.” Her imagery has captured the weight of the icebergs in Alaska and the sky in the Arctic Circle. It’s a study of scale and time that feels a lot like a gust of migratory birds; a reminder that time is fleeting and eternal, and that we have always been a part of it. It also maps the interconnectedness of her past and present, her journey from land to sea.

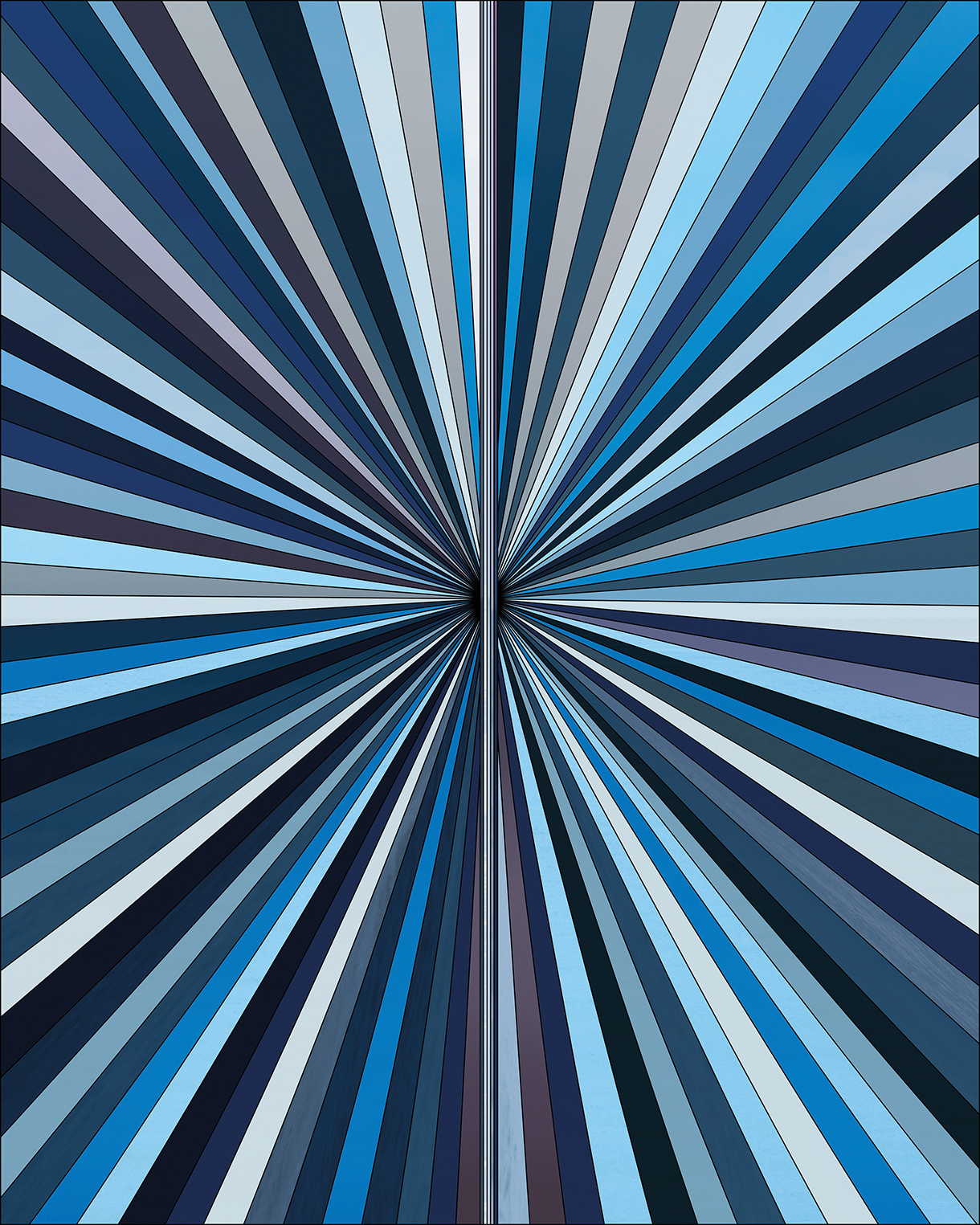

The influence of geologic inquiry—the way it fuses science and intuition, logic and non-logic—is evident in The Library of Sea Colour, Hamilton’s collection of 16,000 images that comprise the world’s most comprehensive catalogue of natural maritime color. In the spirit of the scientific method, the project began with a question: What would happen if a single location and perspective on the beach were photographed over and over again?

Working predominantly with a Hasselblad large-format digital camera, Hamilton began documenting the natural light, deliberately shooting within three f-stops. Sometimes the sky was cloudless, other times misty. But always the photos were unaltered, and always they encouraged her to leap from the realm of precision into what she calls “the magic” through the colors they revealed.

For millions of years, humans have stood on the ocean shores and looked toward the horizon, observing the same infinite dimension of color that Hamilton was capturing. Yet what she found herself wondering was whether the emotion tethered to those colors could somehow be captured, too. Her forthcoming online platform, The Colour Project, is the response to this question. It will refract color through the lenses of language and art. “Someone could say, ‘Oh, I really vibrate with this green.’ And then discover artists and writers, connect with their work, and interpret what they felt about that color,” she explains.

To speak with Hamilton is to experience a real-time slice of this vision—to journey to India and Sweden, delve into the poetry of Emily Dickinson and the fossils of Mary Anning, only to discover how these things connect to a single shade of oceanic gray.

Horizon 101 Blue

What is your earliest memory of the sea?

[That] would be from my birthplace, Lima, Peru, where the water is ice cold, the sand dunes are high, and the air is thick and white due to the Humboldt current. The next would be the Gulf of Mexico, where I spent a lot of my childhood after my family moved to Mexico City. We went to the ocean almost every weekend to escape the business and pollution of the city, and this established a pattern that has stayed with me for life—a need to return to blue spaces. As we continued to move as a family, the ocean came to represent the one constant in our lives. Later, my parents settled in Vero Beach, Florida, and I have been returning to that coastline ever since. I feel lucky I was able to go there during the pandemic and be literally next to the sea.

How has life and your artistic process changed amid the pandemic?

I made a decision that I really just wanted to work, and write, and make things. I’m not as interested in the marketing, the selling, all of that side. I decided that as much as possible, I wanted to free myself. I have all of these projects that I’ve started. There is so much I want to do. So much I want to create and write, and I have a limited amount of time and energy. In a way, that’s what the pandemic has shown me: Choose where you’re going to place your focus.

So meanwhile: [She holds up Canadian psychologist John Alan Lee’s Color Wheel Theory of Love]. I’m finding emotional words for the sea. When I was at Brown University, one of my subjects was comparative literature. Do you know Marguerite Duras?

Yes. The Lover.

I wrote a thesis in French. Thirty pages about the tension between love and desire, Eros and Agape, in the works of Marguerite Duras. And now my current research, this color wheel, literally has Eros and Agape in it. It links them to different colors. I think life is a really weird circle. Everything I did in college, I’m now coming back to. So I’ve just been in this place of honoring that and accepting it as my life’s work. Maybe some ancestors started this and I’m finishing it.

Enchanted Islands No.2

How did you make the leap from studying comparative literature and politics at Brown to life as a full-time artist?

I had a mother who was an amazing artist, but she felt that her role as a mom came first, so she worked as a closeted artist. She did an MFA in Minnesota after we moved from Mexico. Everywhere we went, she was creating, but she always did it in the quiet.

What was her work like?

She painted beautifully. She did more figurative art, but had a great sense with color. It’s so funny that I’m now “Miss Color” because I never liked it. I was a monochrome, black-and-white kind of person. When I was a kid, I did well in school, so my mother was always dissuading me from the arts. She was like, “You need to be like Maggie Thatcher, be a lawyer”—because it’s so hard to be an artist and support yourself. Photography and the darkroom was always this thing I did, but my mom told me I could be an artist later.

So I worked as an intern in Chicago for [Victor] Skrebneski, a fashion photographer, and saw that you had to do catalogues all of the time. I did the law thing but did not like it. I was not fired up. Then I got the job as a rolling equity research analyst. I was on the road traveling, getting to go to all of these mines. I was lucky, because I got to be in nature a lot—really wild nature. But by the time I got to my early 30s, I was like, “It’s time to have babies, retire, and go straight to the dark room.”

And your father?

Even though my dad was in business, he’s really interested in history. He was always keeping photography albums and documenting our life. We have probably 150 albums from Peru and Mexico. He wrote about where we went, what we saw, how we experienced it as a family. We have all of these beautiful albums in leather, they’re almost like sculptures. At that time in our lives, my mom was always taking us to old antique markets. We were always exploring and hunting for treasure. And that’s what The Colour Project is: treasure hunting.

Tidal Resonance No. 17, 2014.

Treasure hunting in what sense?

Imagine you have this leaden gray sea. The thing about gray as a color, is the shades can go a little lighter and be so beautiful. And then darker, the color of ominous clouds, tying it to the weather and to a feeling. In researching that color, it took me to Emily Dickinson’s “After Great Pain, A Formal Feeling Comes.”

I lost my mom to cancer, and what the poem is about is when you lose someone that you really love, you go into this kind of automatic mode. You become machine-like. You’re trying to organize the funeral, but you’re not feeling anything. And you think: Why am I not feeling when I’ve lost the greatest love of my life?

The poem describes “the hour of lead,” and what it says is: it’s okay. It’s okay to be a little like the robot going through the steps, because that’s your protective armor. It’s your survival mechanism, and it’s a part of the process.

So to make the jump from the color in the ocean to a poem that honored an emotion I didn’t know how to express—the experience that happened between those two things, that’s what I’ve been trying to figure out with The Colour Project.

Van Gogh painted the sunflower 11 times. Yellow can veer toward the sun in health and well-being, but it can also turn brown and jaundiced. And there was Van Gogh, painting the sunflower over and over again, and all the while becoming more ill.

Tidal Resonance No. 25, 2013.

Much of your work is captured from a vantage point above ground, but you also used to do underwater photography. What’s it like diving deep into the ocean?

It’s heaven. It’s silent. That’s the most beautiful thing, I think, the silence. When you really get down to the ocean floor and you’re exploring, it’s a whole new world. Probably as exciting as going to the moon. As we know from [marine biologist] Sylvia Earle, there’s so much to learn and so much to understand. But due to bursting my eardrum, this form of exploration has been put on hold.

I was on a dive in Sicily when it happened and no one really told me that once it ruptures, you have to be really careful. There are all of these other things that can happen when the inner-ear is open to the elements. So three years after it happened, I was on a plane back to London [where I live] and the day after I landed, I lost my eyesight completely. I went to see a neurologist and all I could do was sit in a dark room and listen to the radio. For three weeks, I sat there like a lemon and I wasn’t getting any better.

Muskox (Ovibos Moschatus). The Bellows, Discovery Harbor, Northern Ellesmere Island, Nunavut, Canada–American Museum of Natural History, NY.

Hallgrímskirkja, Reykjavík, 2020

How did you recover from it?

I remembered reading about acupuncture, about how it cleared the energy channels. So I called the best place in London, and I said, “Please get me your best doctor.” He came morning and night, morning and night—and I could feel the heat moving across my face. Within a week, I got to the point where I began to see fragmented vision. And from there, it took another year of healing. I went to Florida, to the sun and sea, and I got better. Though I couldn’t go underwater anymore, I thought: Maybe I can look at the surface of the sea forever and examine it that way. One door shuts and another one opens. You can always find a different portal.

Your writing on the ocean, which is so intertwined with your imagery, reminds me of nature writer Rachel Carson’s work.

The thing with Carson is, she’s able to bring [nature] alive in a non-sciencey way.

She has all of the scientific footnotes in the back of the book.

But then she brings the wonder, and that’s what I’m trying to get to: the wonder and the magic and the feeling that we get. What I’ve become interested in is the emotional state we are brought to from the experience [of the ocean], and trying to really understand it on different levels without forcing anything on anyone. Is it the language that inspires us? Or is it the imagery? The music? There’s something really magical in the wave, the energy that’s happening. Through color, a whole world can open up and it can help you understand yourself; it can become a mirror.

Luminous Icescape Iceland No.3