Home’s New Frontier

Residential architecture is moving into a new era, driven by advances in 3-D printing and environmental technologies that address evolving live-work space realities.

JINHAI LAKE, BEIJING

Architecture: Tighe Architecture, tighearchitecture.com; John V. Mutlow Architects, mutlowarchitects.com

Square Feet: 10,300

Bedrooms: 6

Solution for Tomorrow: A faceted form that captures light and passive heat in unusual ways while preserving complete privacy for the building’s occupants

In an era defined by Zaha Hadid and Frank Gehry, unusual architectural geometries aren’t new. But this twin villa has specific reasons for its idiosyncratic faceted form. First, says Patrick Tighe, “We wanted to take a very ordinary material for that region—concrete, which we perceive as big and heavy—and create a striking form articulated in a way that feels light.” It also tweaks ancient Chinese courtyard home typologies in a contemporary way, creating a central, glass-sheathed void that, Tighe explains, “is the connector that allows for circulation between the homes, as well as ventilation and circulation of light.” Windows that resemble fissures among the facets give views a sculptural quality. Aside from maximizing passive heat, the natural light enters in intriguing ways to animate rooms with a play of light and shadow. The villa is buried into the ground, creating thermal mass, so it’s cooler in summer and warmer in winter.

ABU DHABI, UNITED ARAB EMIRATES

Architecture: Peter Pichler Architecture, peterpichler.eu

Square Feet: About 37,700

Bedrooms: 7

Solution for Tomorrow: Culturally derived, site-appropriate forms and motifs for thoroughly contemporary living

Six is a providential number in Arab architecture. It determines the sections of mosque domes, and it’s showcased in the hexagons of lacy mashrabiya screens, which invite in light while preserving privacy. This villa, to be completed in 2023, uses the number to tweak the archetype of a single-family Arab residence. Architect Peter Pichler created six buildings he calls “rocks,” which he positioned around a courtyard—the central feature of Arabic residences. The angular rocks create “canyons” between them that mimic the surrounding desert. Each limestone-clad trapezoidal structure serves a different function. Clockwise from the entry, there is the men’s majlis (a gendered social space), a kitchen, a fitness center, a larger “rock” accommodating bedrooms and family spaces, a dining room, and, finally, the women’s majlis. Natural light filters through powder-coated aluminum mashrabiyas.

“The home is a contemporary interpretation of vernacular architecture, incorporating specific cultural norms and traditions of place,” says Pichler.

ANYWHERE, EARTH

Architecture: Terreform ONE, terreform.org

Square Feet: Variable

Bedrooms: Variable

Solution for Tomorrow: Living plants as building material that “grow” homes over a basic armature

“There’s no more future in building with carbon-intensive concrete and steel,” says Mitchell Joachim of Terreform ONE. “These materials played a significant role in decimating our biosphere. Growing homes with living materials is the most effective way to dwell sustainably on this planet.” The idea is to create and graft an aluminum armature onto existing trees that directs the growth of young woody plants, which eventually become the primary structure and building material of the residence. “It’s more than being sustainable,” says Vivian Kuan, executive director of this innovative architectural research and urban design group. “It’s the idea of growing things rather than depleting our natural resources. It’s a positive contribution to the environment.” The group foresees extending ELM (engineered living materials) to interiors too. “What if we could actually grow our furniture using mycelium? Grow our homes out of actual plants?” she asks. What if, indeed?

LONDON

Architecture: Undercurrent Architects, undercurrent-architects.com

Square Feet: About 2,150

Bedrooms: 3–4

Solution for Tomorrow: Reclaimed green space and sensitively designed housing in dense urban centers

Innovative architects and urban planners are reclaiming and creating green spaces in densely populated cities, bringing life into even the densest of concrete jungles. That’s what London did in the 1980s, when the city rewilded a decommissioned railway running through an ancient ring of hills that had been lost under pavement. The concept for this structure, dubbed “House of the Lost Forest” by Undercurrent’s founder Didier Ryan, proposes Douglas fir slat siding that “provides pattern, depth, and texture in a very natural way.” Dark slate areas frame vertical, cathedral-like windows facing the woods and emphasizing the connection between the oak and ash treetops and understory habitat now populated by bats, owls, foxes, and deer. “Planting woodland, rather than planting a traditional garden, creates a broader ecosystem,” Ryan says. “Luxury doesn’t necessarily equate with wide-open space and the absence of neighbors. Here, it’s a centrally located, highly personalized space, connected to both nature and the city.”

RANCHO MIRAGE, CALIFORNIA

Architecture: Ehrlich Yanai Rhee Chaney Architects, eyrc.com; Mighty Buildings, mightybuildings.com; Palari Group, palari.com

Square Feet: 864–1,440

Bedrooms: 2–3

Solution for Tomorrow: 3-D-printed prefab housing that is affordable and can be built quickly

The innovation of 3-D-printing technology has taken prefab housing to a new level. The first 3-D-printed house happened in Russia in 2015, and a Dutch firm recently delivered keys to the founding residents of a 3-D-printed community in the Netherlands. In the United States, a new community of Mighty Homes is currently taking shape throughout California, including a multi-unit development in Rancho Mirage designed by Palari Group. Made of panels that are flat-packed à la IKEA and shipped to the site of a pre-built slab foundation, the process reduces construction times from an average of nine months to nine weeks, says EYRC Architects partner Mathew Chaney. “The material is like a resin-impregnated powder similar to Corian. The highly resilient panel is spray-foam-injected into a honeycomb matrix. It becomes the exterior and the water barrier in one.” Wood-frame houses are “nowhere near as resilient” and cost much more to build, making these prefabs relatively affordable. The design can also incorporate solar panels.

RED ROCK, UTAH

Architecture: Superficium Studio, Ltd., superficium.com

Square Feet: Adaptable

Bedrooms: 15 (as seen here)

Solution for Tomorrow: 3-D-printed biopolymers and bioplastics to be used as building materials

Last year, Superficium co-founders Samuel Esses and Jon Wong entered an architectural competition with a broad directive: generate ideas for the homes of tomorrow. Their Biohacker’s Residence, says Wong, “expands the idea of at-home, DIY biology labs beyond something that’s done in garages.” Rather than steel and glass, every aspect of the structure would be 3-D-printed using biopolymers and bioplastics that appear as boulders in the desert.

At the center of the individual bedrooms is a communal open lab where DIY biologists can exchange ideas and experimental practices. Esses notes: “It’s a retreat outside the city, a protective, but also enabling, space where biohackers can operate out of the public eye, but that also supports their emerging practice. The skin is like a cellular organization and allows you to take more ownership of your space based on user needs.” Additionally, they envision the space being responsive and adaptable to the user’s occupancy and environmental comfort, enabled through advanced 3-D printing technologies.

ISTANBUL

Architecture: Carla Bonilla Huaroc, carlabonilla.net; Samia Kayyali, skayyali15@gmail.com

Square Feet: 160–215/one-bedroom unit, plus 430/common space

Bedrooms: 1–2/module

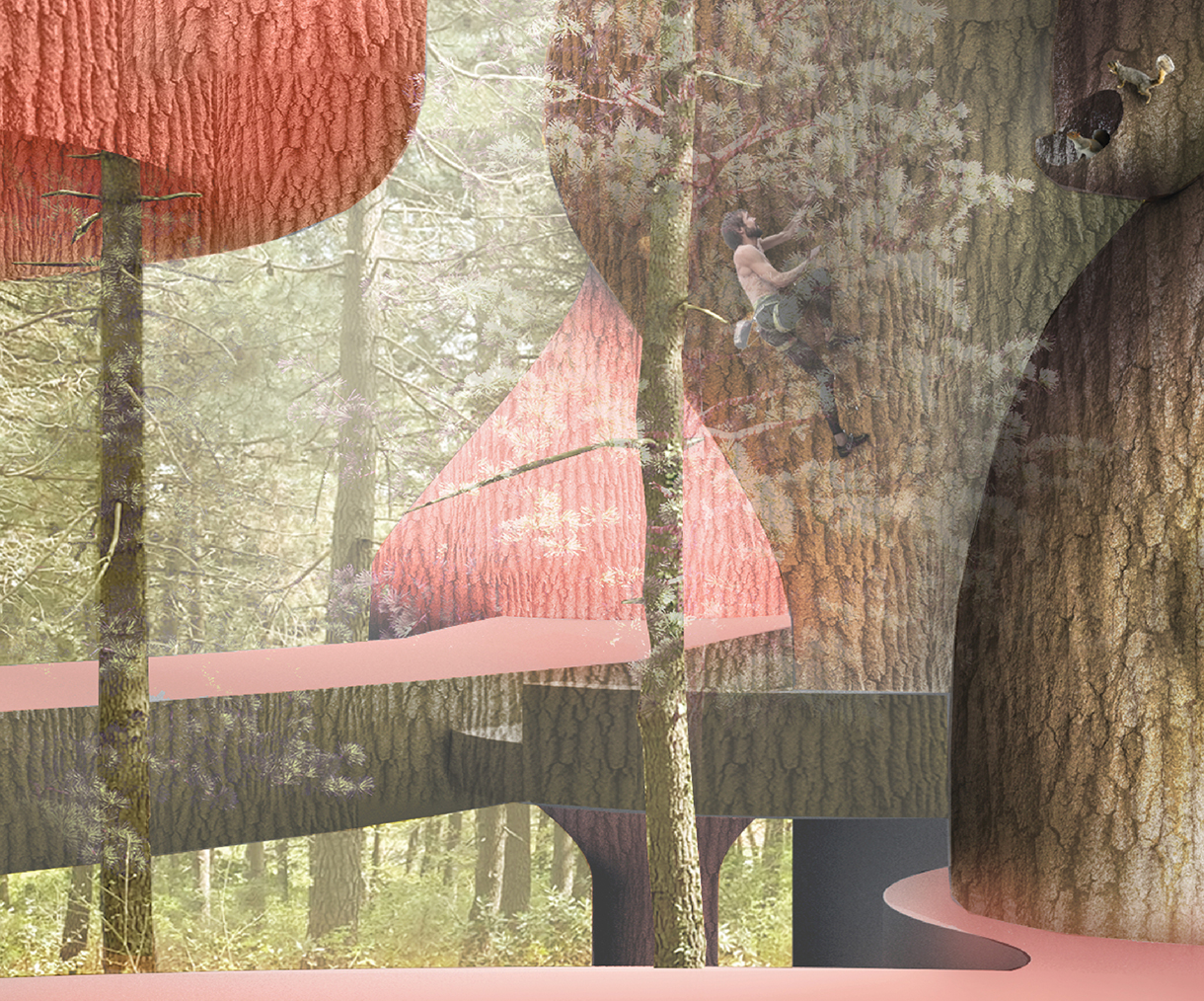

Solution for Tomorrow: Modular treehouse design devised for the cohabitation of humans and native animal species

“Many forests around Istanbul are being wiped out to accommodate development,” says Architectural Designer Carla Bonilla Huaroc. She and architect and landscape architect Samia Kayyali responded with a concept for treehouses made of individual bedroom-bath modules connected by looping pathways to a common living space, as well as various recreational spaces. Made of 3-D-printed ECOncrete, an aggregate material containing recycled waste products, the fantastical forms of the modules accommodate humans as well as squirrels, lizards, and birds. “The walls have pockets built into them in sizes and shapes informed by the form of the habitats that the different species build for themselves,” Bonilla says. This provides habitat for both humans and native species. The project, she says, “negotiates the relationship between what’s already there—the forest—and inhabited built space.” Some of the modules would use the trees themselves for support, while others would have footings on the ground. The community can be expanded throughout any forest.

THE MOON

Architecture: Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, som.com with European Space Agency, esa.int

Square Feet: 1,120

Bedrooms: 4–6

Solution for Tomorrow: Lunar habitat with open central space that is nearly dwell-ready upon landing

Rather than resorting to 3-D printing like many proposed lunar dwellings—which requires equipment and human supervision over some time—the basic module for this Moon Village, planned for the rim of the Shackleton Crater, is inhabitable after inflation and some relatively easy setup. It’s like prefab housing for outer space. Once modules are set down on the surface and the shells inflated, they offer complete environmental protection. They also harness near-continuous daylight for energy, and for growing consumables. Frozen volatiles and water stored in the crater can be tapped for life-sustaining resources and rocket propellant. Finally, modules are designed to be interconnected, enabling free circulation. “Designing a self-sustaining settlement on the Moon in such a hostile environment will teach us invaluable lessons about sustainable and resilient design,” says SOM Design Partner Colin Koop. “It will help us prepare for a changing climate on Earth and pioneer new methods of building for a variety of environments.”