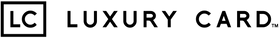

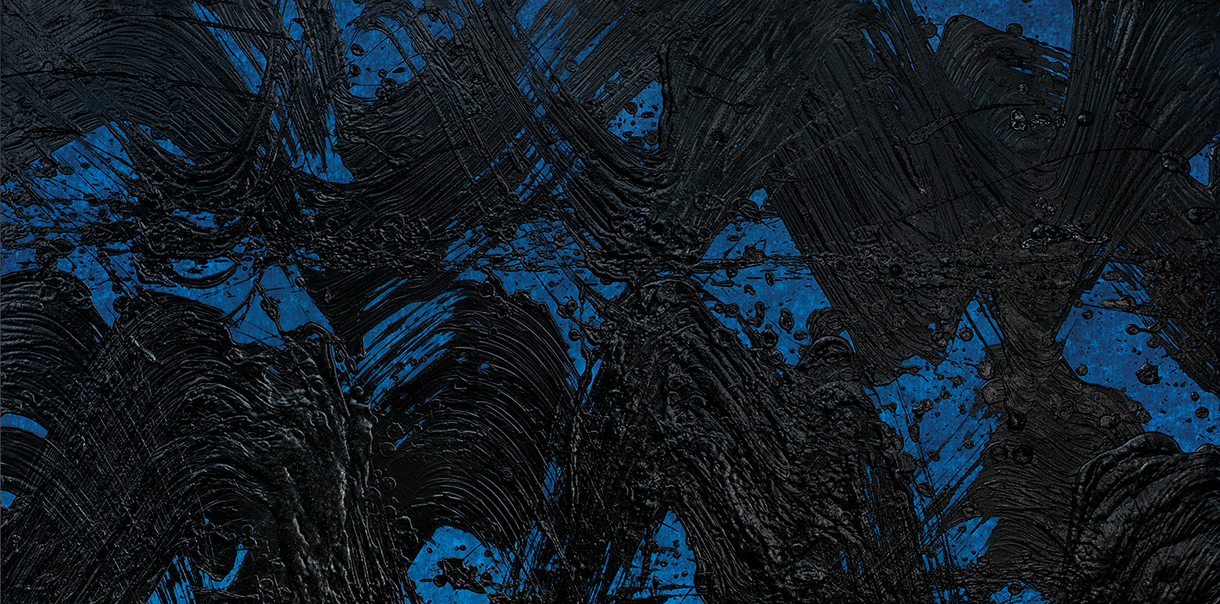

Mutation, 2016, acrylic and mixed media on canvas, 72.5 x 160 in.

Fabienne Verdier

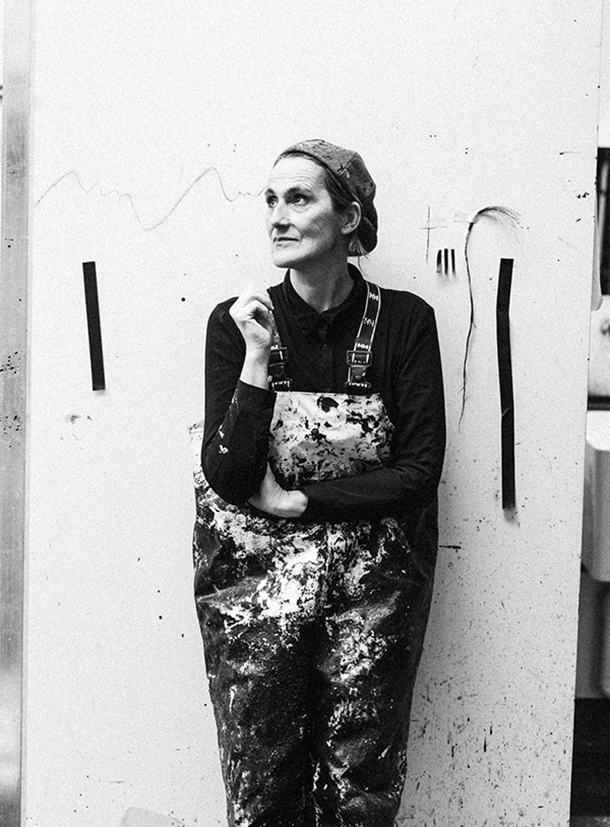

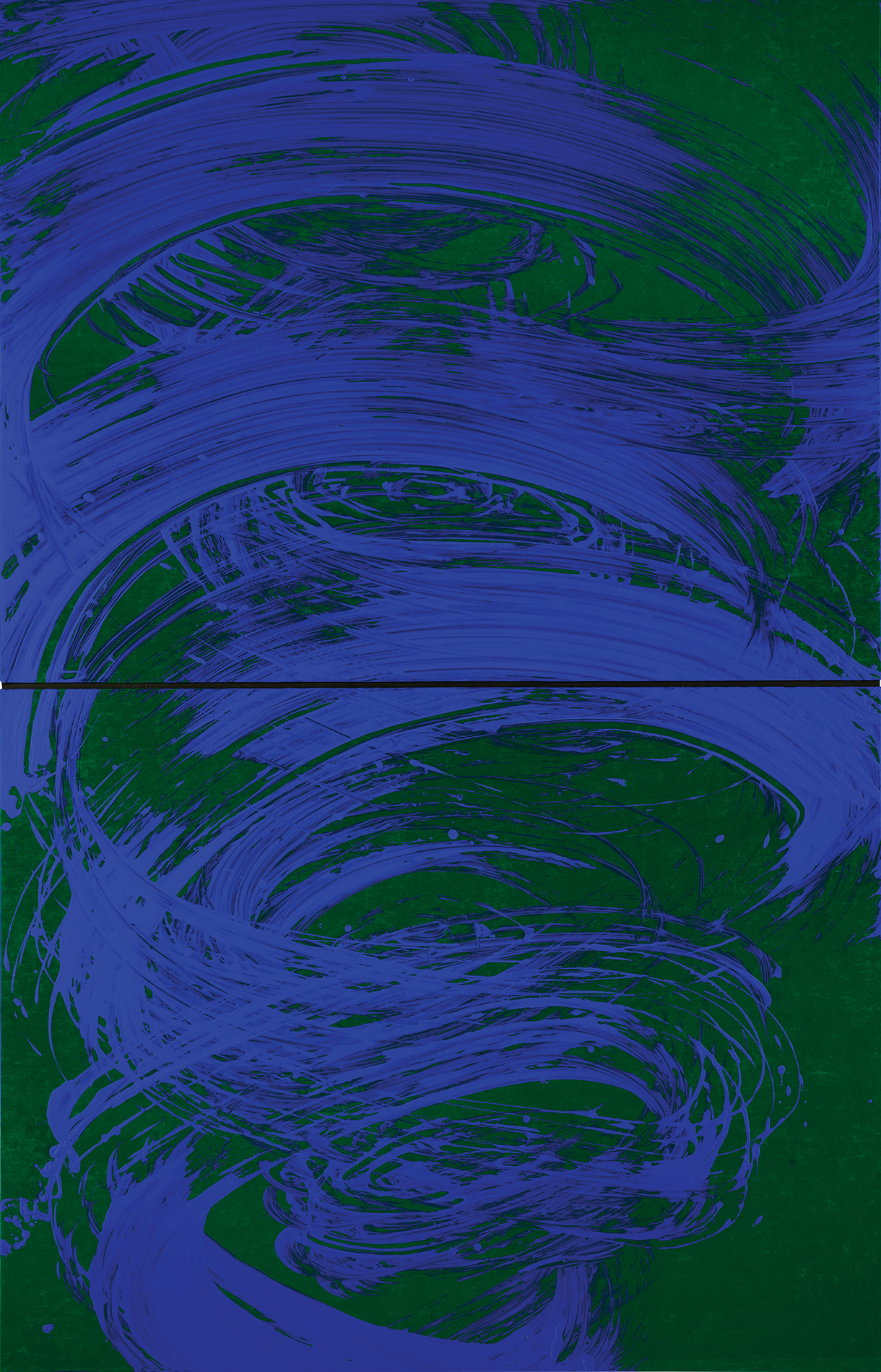

Deh, Vieni Alla Finestra, 2020, acrylic and mixed media on canvas, 72 x 53.125 in.

THE SPIRIT OF FORM

French painter Fabienne Verdier’s lifelong quest to understand energy and movement took her from France to China in search of the master painters martyred during the Cultural Revolution. What she discovered comes to life in her works.

During her first meeting with the teachers at the Sichuan Fine Arts Institute in 1984, the artist Fabienne Verdier was handed paper, an ink stone, and a brush. “Paint a tree,” she was asked. “We’ll see your level, what we can teach you.”

At 22 years old, Verdier had journeyed from France to China’s Sichuan province in search of the last living masters of traditional Chinese painting—the keepers of culture and technique thousands of years old.

“I was interested in movement and spontaneity,” says Verdier, who attended École des Beaux-Arts in Toulouse. “But this sort of thing wasn’t taught in France and my professors suggested I go to Asia where I might find this approach, this way of manipulating the paintbrush to represent the spirit of the living through the energy of the stroke.”

Standing before her new teachers in China, Verdier found herself straddling two worlds. “For us Europeans, if we want to paint a tree, we take our sketchbook, do a study, and imagine a composition.” For the old Chinese masters, the expectation was to capture the spiritual essence of the tree. “To paint the spirit of the tree you have to become the tree. You have to imagine the sap’s surge and capture with your paintbrush this sap’s push toward the light.”

When Verdier asked for a few weeks to complete the assignment, the Chinese teachers laughed. “OK,” they told her. “You’re starting over.”

In order to immerse herself in the ways of the East, Verdier had to undo the ways of the West. “I had to dismantle all of whom [I’d been before] so that I could find a broader field of perception where there were no longer boundaries between me and the world.” She had to learn how to close her eyes and find the tree within.

To listen to Verdier speak is to intuit her 10 years in China and the 30 that have followed as part of a process of becoming whole. To look at her work is to experience the wholeness viscerally. Large-scale, abstract paintings are characterized by gestural brushstrokes made using enormous, vertical brushes that fuse the East and West. In her Walking Painting Series, bolts of black acrylic reach across carefully prepared canvases—their essence unmoored yet contained, harmonious yet tension-filled, dark yet electric, fluid yet fixed, strenuous yet delicate. The paint holds the shape of many things: lightning, tree branches, a snaking river, the chasm of a quaking earth, and the energy force that courses through all these things. Though the paint is dried, the movement is alive. Like petrified wood, death and life are suspended in a state of exquisite forever.

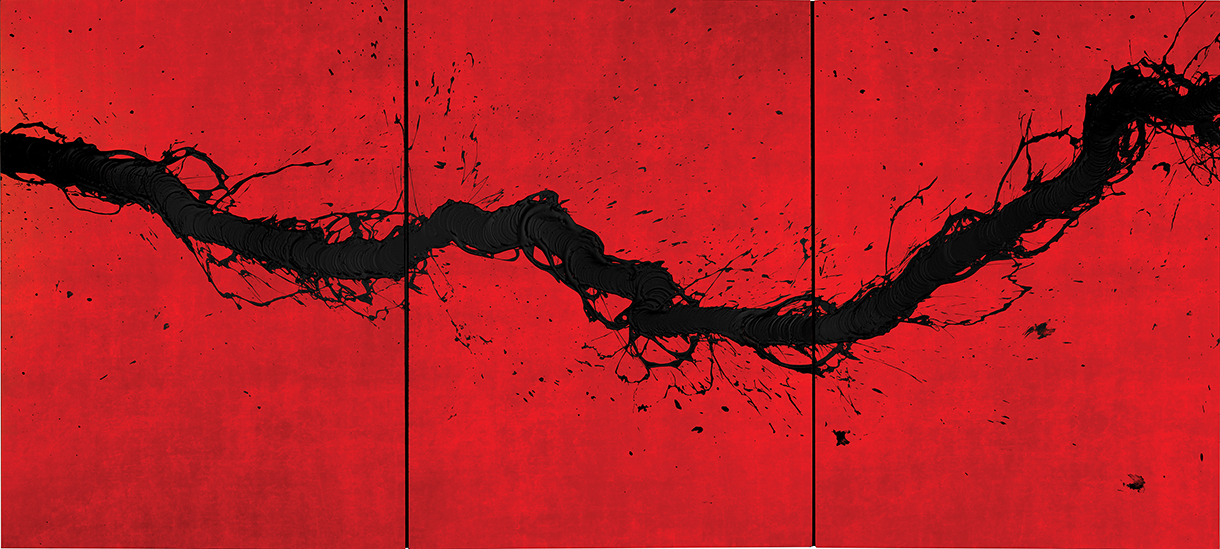

In late September, Verdier was home in Vexin, north of Paris, where she works from a studio designed around the brushes that hang from the ceiling. She has kind, patient eyes and tufts of gray hair, and as she spoke about where this moment in life currently finds her, it became increasingly easy to see nature itself peering through her being. The lines on her face, poised and generous, were like the ones that wise oaks age into. Stillness emanated from the inside out.

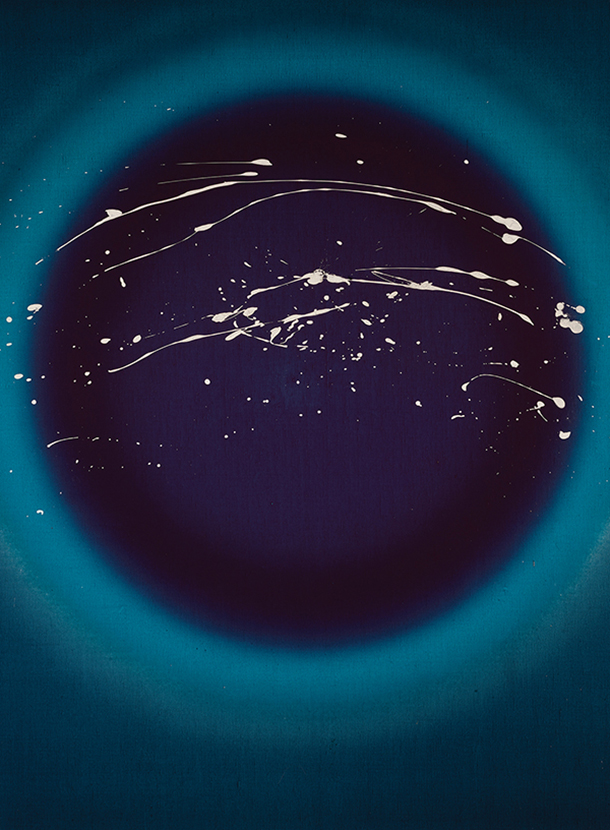

Erkhes, Эрхэс - Mongol Galaxie, 2022, acrylic and mixed media on canvas, 72 x 53.125 in.

INTERVIEW WITH FABIENNE VERDIER

What is present in your art and life right now?

It’s curious, I feel I’m in a sort of shock in the face of the unprecedented violence of our societies. Barbarism, wars, the suffering of people. The exhaustion of our little planet. And for the painter that I am, it’s about becoming resilient and acting for the living. This is where I want to give all my strength, as if it were an inner necessity. After these long past years of confinement, after the whole COVID period and working in the studio around death for my last exhibition, Le Chant des Étoiles, I currently aspire to paint a kind of rebirth—like a wild desire to capture with my paintbrushes the sacred part of life. I’m currently absorbed in the creation of triptychs whose two-sided panels can open or close like the wings of a butterfly.

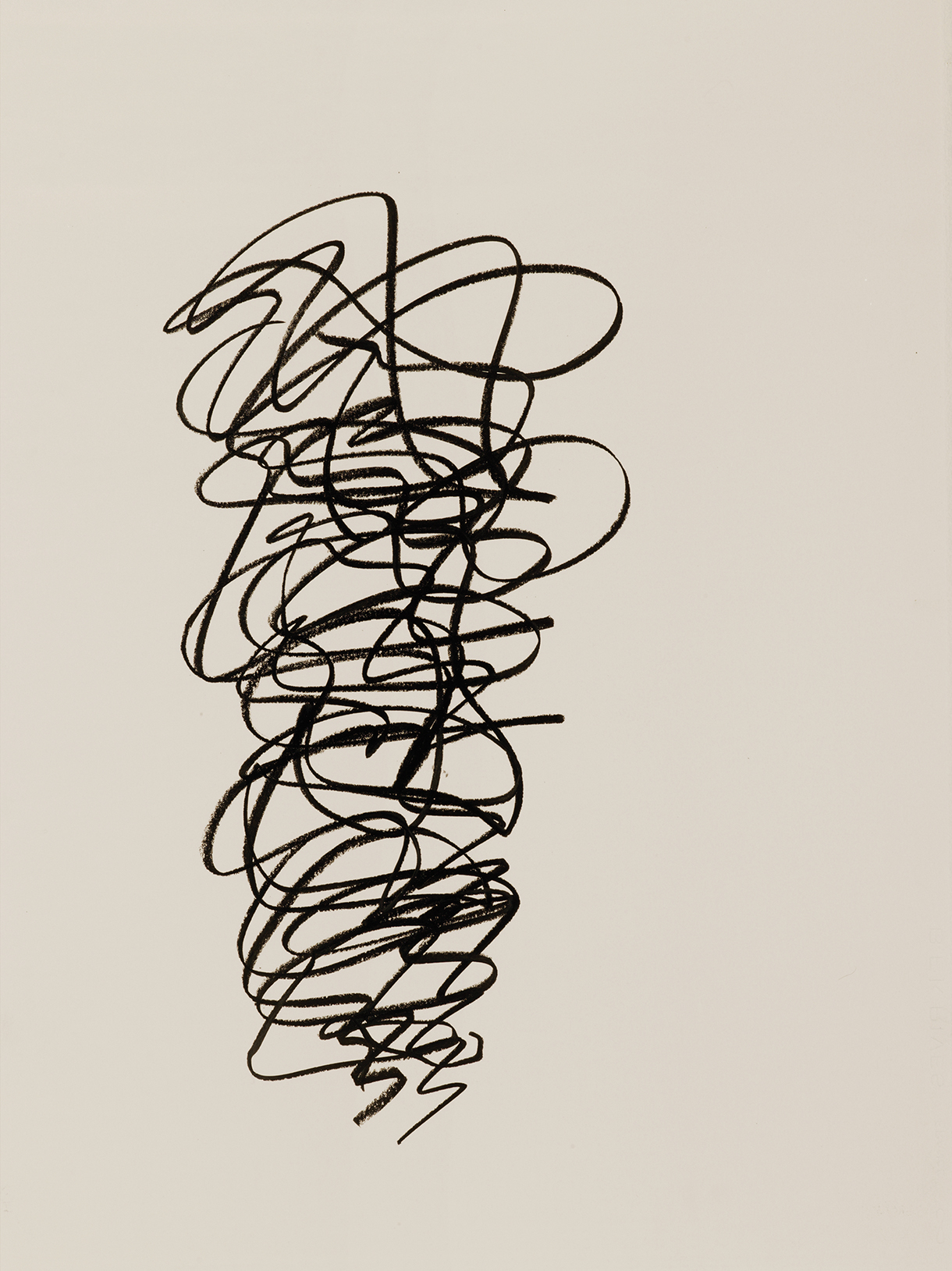

Voice Breath Column III, (Edith Wiens Class 12.2014), 2014, oil pastel arches on vellum, 31.5 x 24.5 in.

How is the circularity of life and death alive for you?

There is no real death. We are beings in constant transformation and it’s something extraordinary. When I became interested in the subject of death, it was through Matthias Grünewald’s Isenheim Altarpiece. In it, there is a panel of the resurrection where an unexplained and extraordinary aura of light is behind Christ, and this Christ is being consumed and disappearing. It was the body undergoing transformation toward death and changing into light, luminous energy. So, I began to reflect on this transformation of the human body.

Scientists tell us we are of stellar essence, that we are stardust and beings of light. I listened to an astrophysicist once who spoke of the death of stars. He said that when stars are very old, they can no longer resist their center of gravity. They collapse in on themselves and by collapsing, they implode. While imploding, depending on their physical matter, an extraordinary aura of light emerges. From this aura of light, the microparticles of matter melt into nature and there’s no real death of stars, as from this accumulation, new stars are born. I found this very beautiful—to imagine a body of work, new icons in painting, that compare human death to the death of a star.

How does your creative process unfold?

For each series of paintings, the genesis always lasts two or three years between the first contemplations. There are initial draft writings, sketches, research in my notebooks, workshops, and an almost scientific research process to see how this subject has been addressed over the centuries. I want to see how our generation can bring a new perspective to the topic. It’s always a long birthing process.

What about the actual painting itself?

A painting begins by creating a background. By background, I mean a vibrating pigment field. For the series I’m currently working on, I start with layers of very luminous silver or aluminum, then apply random deposits of glazes in the most transparent colors possible, using fine silkscreen printing screens. My aim is to optimize the refraction and vibration of light on the color pigments, so that they can vary once the work is hung on the wall, as the day’s light changes.

How integral is daily ritual to all of this?

One really has to step aside from the life of the world and society, and lead a life that is very ordinary, with extremely ascetic hours. There are hours of rituals, work, meditation, and contemplation that nurture the moment when I’ll grasp the clouds of paint and strike the form. To attain that mastery, it’s immense work.

Polyphonie 1, 2015, pigment ink and varnish on canvas, 35.5 x 70.825 in.

What were your most formative early experiences with art?

Visits to the Musée d’Art Moderne in Paris as a child. My father moored his houseboat on the quay below the museum. Every weekend was devoted to discoveries: Jean Tinguely’s machines, Niki de Saint Phalle’s women, Takis’ installations, Yves Klein’s blue monochrome backgrounds, Lucio Fontana’s notches, and so many other things that fed my childhood imagination.

Your father was an artist.

He was the artistic director at an advertising agency. He made that commercial with Salvador Dalí: “Je suis fou du chocolat Lanvin!” [I’m mad about Lanvin Chocolates!].

When did you realize you wanted to become an artist?

At around 15 or 16 years old. That’s when my father said to me: “Painting is serious, let’s see if it’s what you really want to do.” We went to the garbage dump, picked up some old iron pots, brought them home and he said, “You paint them. Lock yourself in a room and we’ll see what the results are in a few days.” He must have thought I’d give up, but months later I was still trying to paint those pots. He realized there might be some hope and allowed me to enroll in art school.

Aiguilles de Bavella, 2022, acrylic and mixed media on canvas, 46.5 x 70.125 in.

Westerners had rarely traveled to the Sichuan province since 1949. What compelled you to go?

It was the era of conceptual art in the ’80s, and there wasn’t much instruction for painting anymore. There was one drawing teacher, however, who detected a certain vitality in my line. I wanted to capture birds in motion, and he suggested I take up animal painting. I spent my days looking at stuffed animals in the windows of the Museum of Natural History. I began to immerse myself in books on Chinese and Japanese painting, where I saw that painters had achieved great vitality with just a few brushstrokes. My teacher told me that they didn’t teach that here and that I should go to Asia. And that’s when I decided to study in China.

What were some of the greatest lessons you learned there?

I hadn’t realized that I was entering a very harsh, totalitarian system just 10 years after the Cultural Revolution. And so, I found myself even more confined at 22 behind the [barred] windows of a small office that the school had transformed into a student room for the only foreigner they had at that time. There, the old Chinese masters taught me introspection. That is, I was alone with myself, and I couldn’t easily go outside alone to paint reality, nature. I had to close my eyes and learn this introspection.

In the West, there is man and there is nature. The traditional culture of the ancient [Chinese] masters tells us that man and nature are one, that there is no difference. The universal energy that is around you and that you want to paint ... it is in you. It is in the river, it is in the tectonics of the mountain, it is in the movements of the wind, it is everywhere. You are part of this same universal energy, so if you close your eyes, take your brush, and paint this universal energy, it runs through you. When I think about it, it’s as if I’m melting into the subject. It’s as if I, Fabienne Verdier, become the tectonics of the mountain, I become the turbulence of the air, I become the subject that I am painting. It’s a great liberation of the ego, a great freedom.

In China, did you ever sense that you’d been there before? Did any of it feel familiar?

No, the education was very challenging. For centuries in the West, we’ve been taught to construct the world through the vanishing point, the Euclidean way of thinking. In Asia, I discovered that in the act of vertical painting. The point becomes a vertical gravitational point between heaven and earth. It’s a painting of flow.

Ti Ricorda Il Primo Amor, 2020, acrylic and mixed media on canvas, 83.5 x 54 in.

A painting of flow because the canvas is on the ground?

Yes. Jackson Pollock was one of the first to understand this in his drippings. There was a vertical flow of material, and when he set up his canvases [horizontally], he felt a cosmological composition very much in harmony with the forces of the universe.

In their brushes, the Asians invented a kind of reservoir inside. So, when you infuse energy into the brushstrokes vertically, the brush works like a waterfall in the high mountains: It’s a constant gravitational flow and in this flow, you can convey the universal energy that brings life to all forms.

What I find most fascinating in the act of painting is when suddenly my body, the body of the brush, and the axis of gravity become one. At that point, something happens. A force between the powers of the earth and the sky. There’s something at that moment that is beyond me.

One of the giant brushes in your studio has bicycle handlebars attached to it. Why?

I didn’t feel free enough with the traditional Chinese brush, so gradually I modified it. I began to realize that my body itself was in the way when I started wanting to paint vortexes and swirling, centrifugal forces. Suddenly with the handlebar, I was no longer painting with the involvement of my body. [In this way], I discovered a third dimension in the energy of the brushstroke. We were no longer on a two-dimensional plane.

Are there any artists currently inspiring you?

I have great admiration for the 14th-century Russian painter Andrei Rublev, who fought all his life in a time of total barbarism to try to depict universal love in his icons. When we look at his Madonnas, we feel, across all cultures, a sense of peace and a fullness of what our humanity can be—all on one small piece of wood. It’s not a rich art. It’s very simple. To express an inner experience through a brush of three goat hairs ... I find that intriguing.

What lies ahead for you in 2024? What do you look forward to?

I live so much in the present moment. If you are fully in the present moment, you are everything you have been, and within you is already everything you will be.

This interview was translated from French to English. It has been condensed and edited for clarity.