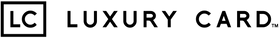

Courtesy Cai Guo-Qiang

Remembrance, chapter two of Elegy, an explosion event on the Huangpu River near Shanghai’s Power Station of Art in 2014.

Cai Guo-Qiang: An Explosion of Art

The Chinese artist harnesses the destructive power of gunpowder to create masterpieces bursting with color and imagery

BY JASON EDWARD KAUFMAN

Courtesy Cai Guo-Qiang

Day and Night in Toledo, 2017, a gunpowder on canvas work inspired by El Greco and measuring more than 9 x 20 feet.

For the 2008 Beijing Olympics, contemporary artist Cai Guo-Qiang directed visual effects at the opening and closing ceremonies. That first night, he orchestrated fireworks forming 29 giant footprints (one for each modern Olympiad) that marched in sequence for 9 miles, culminating at the National Stadium. More than 1.5 billion television viewers witnessed the minute-long display.

Cai came up with the footprints idea two decades earlier, as part of his art series Project for Extraterrestrials. He imagined giants in the universe who could disregard the international borders invented by mankind and believed that to be seen from an extraterrestrial perspective, his work should be outdoors and big enough for extraterrestrials to actually see. “I don’t have specific ideas about any UFOs or alien beings,” he says, “but I believe in the unseen world that exists in the cosmos. I feel it is meaningful and necessary for mankind to be aware that there are eyes out there in the universe looking at us, just as it is for a country to constantly know that there are other countries out there looking at you.”

Born in 1957 in Quanzhou, a coastal city in Fujian Province in Southeastern China, young Cai spent afternoons sitting on a little stool behind the counter of his father’s state-run bookstore. His father had access to the kinds of books that could be read only by members of the Communist Party’s inner circles and Cai devoured them. From the latest developments in foreign literature—Japanese, American, and European writers—to a winner of the Nobel Prize in literature to books about existentialism and the absurd. “They exposed me not only to literature, but to perspectives on humanity and politics,” he says. “I read about hardship in the lives of peasants and workers, and also the romantic side of their lives and their freedom.”

In 1986, with help from an acquaintance who worked in the Forbidden City, Cai emigrated to Japan where he remained until 1995. During this period he established his reputation with large-scale explosion events that led to numerous museum exhibitions in Japan and Europe. In 1995 he relocated to New York, where he continues to live and work. His 15-second Transient Rainbow explosion over the East River sent 1,000 fireworks up in a great arch of thrilling color from Manhattan to Queens. With his pieces, both tangible works on paper or canvas and wondrous public displays, he is the giant traipsing the sky, inciting an awe capable of dissolving division.

Cai is part of the first generation of Chinese artists to gain prominence on the international stage, and unlike many who conformed to the prevailing taste of the Western market, he imbued his work with Asian concepts and materials. His ideas and iconography spring from Chinese mythology and history, Eastern philosophy and religions, Maoist revolutionary ideas, Chinese medicine, and feng shui. He also finds inspiration in Western thought, particularly astrophysics and art history, and mingles the perspectives of East and West.

His ghostly gunpowder drawings make use of a material invented in China, but often represent motifs familiar in the locale where he exhibits them: a eucalyptus tree in Queensland, a Botticelli in Florence, and an American eagle landing on a pine tree (symbolic of Chinese tradition) for the American Embassy in Beijing. Using gunpowder—the fuel of war—Cai channels beauty and reflection through his creative process.

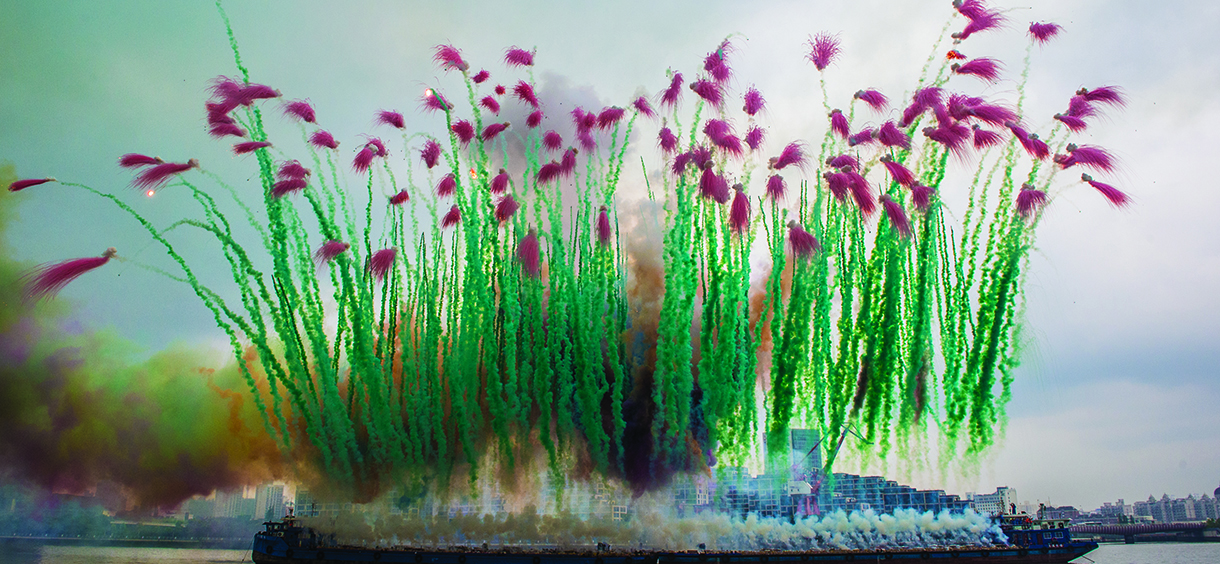

Photo: Jason Edward Kaufman

Cai Guo-Qiang in his New York studo.

Courtesy Cai Guo-Qiang

Footprints of History: Fireworks Project for the Opening Ceremony of the 2008 Beijing Olympic Games.

The centerpiece of his 2008 retrospective at the Guggenheim Museum in New York was a stunning coup de théâtre of nine identical automobiles suspended from the roof of the rotunda, each bursting with rods of blinking colored LEDs. Positioned topsy-turvy in midair, the cars look like a time lapse of an exploding car, an image acutely resonant at a moment focused on the scourge of terrorism. A more tranquil piece made in 2013 for the Queensland Art Gallery of Modern Art positioned sculptures of 99 animals, predators and prey from around the world, drinking from the same watering hole, stand-ins for the artist’s vision of social harmony on earth.

Growing up, Cai studied social-realist painting and belonged to troupes that produced art and cultural propaganda promoting Maoism. As a student at the Shanghai Theater Academy (1981–1985), he worked in stage design and turned from traditional Chinese art to Western forms, including oil painting. Intent on developing his own innovative approach, he experimented with new techniques and began making images with burning gunpowder. Early results were basically white and black. Then Cai added yellow, brown, a rusty orange, even blue. His compositions are more deliberate than you would guess from art made by an explosion. While some look abstract, others show mountains or a crocodile gobbling up

the sun.

When creating a large work on paper or canvas, Cai begins by sketching. He adds segments of fuse and sprinkles granular explosives by hand, then lays down stencils, plants, or other items whose forms he wishes to record. He scatters more gunpowder to adjust the composition and assistants cover the entire setup with cardboard weighted down to contain the ensuing combustion. Once everyone is clear, Cai ignites a fuse, steps back, and seconds later a hissing eruption rolls down the length of the drawing. Fire boils along the edges, acrid smoke fills the air, and his team races in to tamp down flames. The cardboard is removed and the artist surveys his creation—a ghostly image as if rendered on sandstone with the residue of the thrilling blast.

In the past several decades, Cai has been the subject of exhibitions at prestigious museums from the Guggenheim Bilbao (the museum’s first retrospective devoted to a Chinese artist) to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York (his was the Met’s first solo show by a living Chinese artist). His newest works respond to masterpieces of Western art and have been presented in the Pushkin in Moscow, the Prado in Madrid, and the Uffizi in Florence. The 2017 Prado show included gunpowder drawings in homage to El Greco, one of his favorite artists. Last year’s Florence show featured a 15-minute spectacle of 50,000 fireworks, many of them flower-shaped and inspired by Botticelli’s La Primavera. For an exhibition at the National Archaeological Museum in Naples (through May 20), he conducted an explosion event in the amphitheater at Pompeii to echo the ancient city’s volcanic destruction. Next on his busy calendar, Cai will act as curator as one of six artists chosen by the Guggenheim to select works for Artistic License: Six Takes on the Guggenheim Collection (May 24, 2019–Jan. 12, 2020).

For all his success, Cai is not a major presence in the art market. Large gunpowder drawings have topped $1 million on the rare occasions when they come up for auction, and multiple-drawing sets have sold for $9.5 million, but he eschews the gallery system, preferring to sell directly to museums and collectors. His base of operations is a multi-story studio in a former school on the Lower East Side of Manhattan. He and his wife, Hong Hong Wu, also spend time with their two daughters on a farm in New Jersey, where he maintains a second studio and commissioned a house designed by Frank Gehry.

At the New York studio assisted by an interpreter (Cai has never mastered English), the artist spoke about gunpowder, growing up in Communist China, his belief in the unseen, and the complexities of creating large-scale explosion events.

Photo: Steven Oakes/Alamy

Partial view of Unmanned Nature, 2008, a 13 x 147 foot gunpowder drawing commissioned by Hiroshima City Museum of Contemporary Art, installed at The Whitworth in Manchester in 2015.