Collection Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, New York; Charles Clifton Fund, 1972 (1972:5)© The Kenneth Noland Foundation / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY. Image courtesy Albright-Knox Art Gallery.

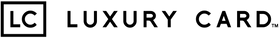

Wild Indigo, 1967. Acrylic on canvas; 89 x 207 inches

Taking Aim

A bright spot among America’s postwar painters, KENNETH NOLAND composed spare geometric designs to explore the interplay and impact of color.

BY JASON EDWARD KAUFMAN

In 1963, Vogue published a photograph of the Manhattan apartment of influential art critic Clement Greenberg. Hanging above his desk, where he would see it every time he looked up from writing, was a large painting of concentric circles. At the time, Greenberg was the Svengali of contemporary art, arguing that to be truly modern, artists must reject representation entirely and pare down the medium to its essence, avoiding figurative drawing and references to the outside world. He envisioned an art formed only from the most basic elements of painting itself: color on a flat surface.

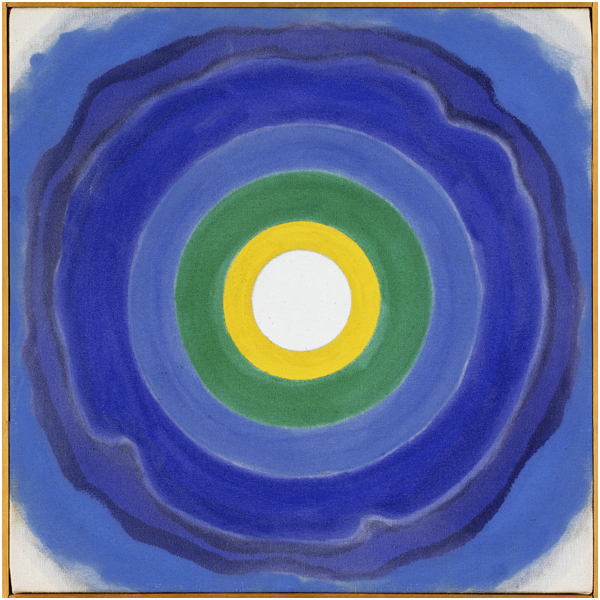

In the late 1940s, Greenberg championed Jackson Pollock’s abstract drip paintings, and in the 1950s he advised painters to advance even further toward his ideal of painterly purity. His acolyte Kenneth Noland (1924–2010), who made the circles hanging above Greenberg’s desk, heard the critic’s words like marching orders. “I would take suggestions from Clem very seriously,” he said, “more seriously than from anyone else ... I’m grateful for it. I’ll take anything I can get that will help my art.” Noland expressed his gratitude by giving the 1961–62 painting—originally titled Clem’s Gift—to Greenberg, who loaned it to important exhibitions (always crediting a “private collection” to conceal his ownership). In turn, the powerful critic’s support contributed significantly to Noland’s critical and commercial success, helping to make him one of the more highly regarded American abstract artists of the second half of the 20th century.

His pictures are in top museums in the United States and in Europe, and major works command multimillion-dollar prices. His auction record is $3.5 million, set at Sotheby’s New York this past May, for the 1960 painting Blue, a 5-square-foot image of red, white, and blue rings around a black core on a sapphire field. A 1958 painting, roughly the same size and subject matter, had previously sold for $3.37 million. Other late 1950s targets, as the series is known, have brought around $2 million. Smaller versions sell in the mid-six figures, and pieces from another series known as chevrons also have topped $1 million. Later works command lower sums — a green and blue target from 1999 sold for $325,000 in 2019—and works on paper might bring $2,000–$10,000.

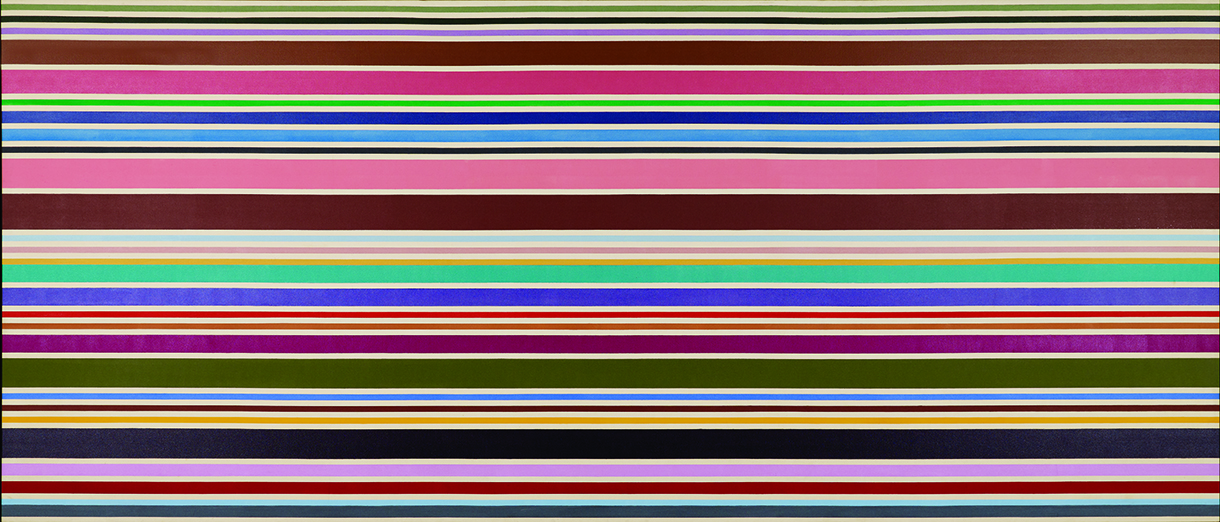

Collection Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, New York; Gift of Seymour H. Knox, Jr., 1976 (K1976:4.31).Fred W. McDarrah (American, 1926-2007). © Estate of Fred W. McDarrah. Image courtesy Albright-Knox Art Gallery.

Kenneth Noland, New York 4/10, 1963, 1963. Gelatin silver print; 8 x 10 inches.

Collection Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, New York; Gift of Seymour H. Knox, Jr., 1964 (K1964:6). © The Kenneth Noland Foundation / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY. Image courtesy Albright-Knox Art Gallery.

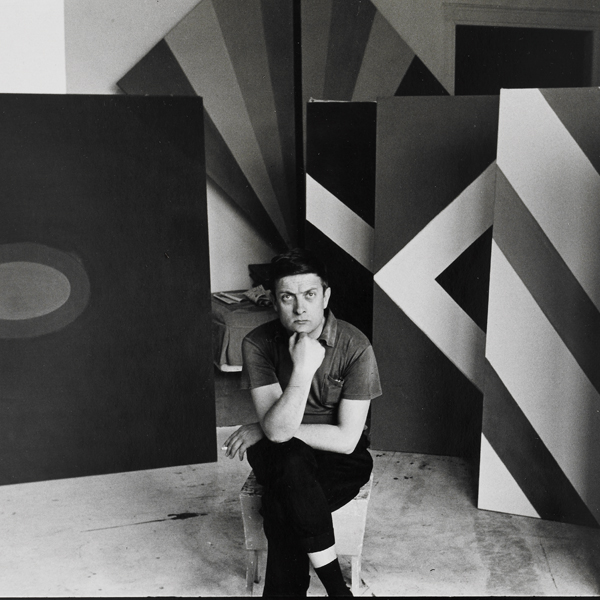

Yellow Half, 1963. Acrylic resin paint on canvas; 70 x 70 inches.

THE BACKDROP

When Noland entered the scene in the 1950s, abstract art was only a few decades old. In the 1910s and 1920s, a handful of European and Russian artists—Kazimir Malevich, Piet Mondrian, Wassily Kandinsky, and others—made the first paintings devoid of people, places, and things, the subjects that artists had depicted for centuries. This radical departure had scientific and spiritual underpinnings and a utopian edge. Abstract artists saw their work as an exploration of perception, a revolutionary way to conceive and construct space, a means of unlocking hidden I dimensions of nature and the cosmos, and even as a universal language. By the mid-century, representational art was passé and “non-objective” abstraction prevailed.

Then, in the aftermath of World War II, American artists sought to distinguish their native art from European traditions. That effort coalesced in the work of Pollock, Willem de Kooning, Mark Rothko, Clyfford Still, and others who became known as the Abstract Expressionists. They made large-scale action paintings that reveled in demonstrative brushwork, and color-field paintings composed of expanses of flat color. Their work was touted as an expression of America’s unbounded freedom, a stark contrast with the socialist realism dictated by Fascist and Communist regimes. Unlike the intimacy of European easel painting, including the modernism of Pablo Picasso and the School of Paris, the new American painting was heroic in size, spontaneous in execution, and romantic in content, tinged with anxiety and violence reflecting the experiences of war and the tensions of the Atomic Age. Noland emerged in this context, just as the United States came to dominate the world art stage and New York replaced Paris as the center of the avant-garde.

FRONT AND CENTER

As a student, Noland emulated the Abstract Expressionists, but guided by Greenberg, his generation took abstraction in new directions. He embarked on a series of almost 200 target paintings featuring concentric rings centered on unpainted canvases. Most, like Greenberg’s Gift, are square in format and measure at least 6 x 6 feet. Some have only a few rings and others eight or more; each has a solid color often separated from the next by a channel of raw canvas. The first targets had textured paint surfaces and their outer rings were surrounded by a loosely painted penumbra that gave them a solar aspect, as though they were spinning and giving off heat. Variations in the early 1960s took on a more machine-made character, with the rings crisply delineated in skins of evenly applied pigment.

Noland’s next series, the chevrons, consisted of parallel V shapes that extend downward from the top of the canvas, their arms of uniform width and each in a different solid color. He modified the series by placing the chevrons asymmetrically on the canvas, making them feel less locked into the frame. In the mid-1960s he started a series of diamond-shaped canvases, followed by stripe paintings composed of horizontal bands of varying widths and colors that stretch across the canvas. Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, Noland made polygonal canvases segmented into hard-edged areas of flat color or covered with linear grids that look like plaid and seem inspired by Mondrian.

Smithsonian American Art Museum; museum purchase from the Vincent Melzac Collection through the Smithsonian Institution Collections Acquisition.

Sarah’s Reach, 1964. Acrylic on canvas; 93 3/4 x 91 5/8 inches.

Collection Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, New York; Gift of Charles W. Millard III in memory of Gordon M. Smith, 1997 (1997:8). © The Kenneth Noland Foundation / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY. Image courtesy Albright-Knox Art Gallery.

Day, 1964. Acrylic resin on canvas; 69 3/4 x 69 3/4 inches.

BETWEEN THE LINES

Noland was not alone in zeroing in on simple compositions. Jasper Johns first painted targets in 1955, and Frank Stella painted monochrome parallel stripes in 1959. Soon French artist Daniel Buren made stripes his signature motif. But more than composition, color was Noland’s main concern. He opted for simple graphic motifs because the viewer could take them in all at once and focus mainly on the chromatic arrangement.

“I was trying to neutralize the layout, the shape, the composition,” he explained in 1977.“ I wanted to make color the generating force.” His palette ranged from subtle harmonies to jarring contrasts, and produced correspondingly diverse visual experiences.

The late critic Hilton Kramer praised Noland’s “sensibility for color ... his ability to come up, again and again, with fresh and striking combinations that both capture and sustain our attention, and provide the requisite pleasures ....He is unquestionably a master.”

Karen Wilkin, author of a Noland monograph, considers him “one of the great colorists of the 20th century.”

“His art was from start to finish an art of color, part of a long tradition that dates in the modern era to Impressionism, runs through Cézanne and Matisse, into the twentieth century, to Morris Louis, and Helen Frankenthaler,” she said.

BIG PICTURE

Noland was born in 1924 in Asheville, North Carolina, far from the center of the art world. His father was a physician and Sunday painter, and his mother an amateur pianist who helped manage a local jazz club. By his teens Noland was dabbling with his father’s paints, inspired by Monets he had seen at the National Gallery of Art. In 1942 he was drafted and served as a glider pilot and cryptographer in the Air Force, stationed mainly stateside, but toward the end of the war in Egypt and Turkey.

After the war, the GI Bill, which funded education for returning soldiers, allowed him to study at Black Mountain College, an interdisciplinary liberal arts school a short drive from his home (two of his four brothers also attended) where he received a crash course in modern art. The school’s director Josef Albers, who had taught at the Bauhaus design school in Germany, advanced a theory of the “interaction of colors,” and Noland’s art professor, abstract painter Ilya Bolotowsky, introduced him to the work of Mondrian. Noland made paintings inspired by Paul Klee, another Bauhaus artist and modern art theorist. But his later exploration of color relations through nested geometric forms is clearly indebted to Albers, whose signature series Homage to the Square began in 1950 and performed the same function in compositions of squares within squares.

After two years at Black Mountain (1946–48), Noland spent a year in Paris studying with the Russian Cubist sculptor Ossip Zadkine and then settled in Washington, D.C., to teach at the Institute of Contemporary Art (1949–1951), Catholic University (1951–60), and at the Washington Workshop Center of the Arts (1952–56)—a night school where he developed a friendship with Morris Louis, another second-generation Abstract Expressionist. In 1953, Greenberg, whom Noland had met in 1950 during a summer session at Black Mountain, brought Noland and Louis to the New York studio of Helen Frankenthaler. She was making Pollock-inspired pictures by pouring thinned paint onto canvas laid on the floor. Noland and Louis took up the approach and experimented with staining canvas. Together they bought rolls of cotton duck from a sailing supplier and large batches of liquid Bocour Magna, a newly invented plastic-based acrylic that could be liquefied and manipulated more readily than oil paint. Louis poured pigment onto tilted canvases forming rivulets of colored “veils,” and Noland used brushes, rollers, or sponges to evenly apply paint to geometric forms.

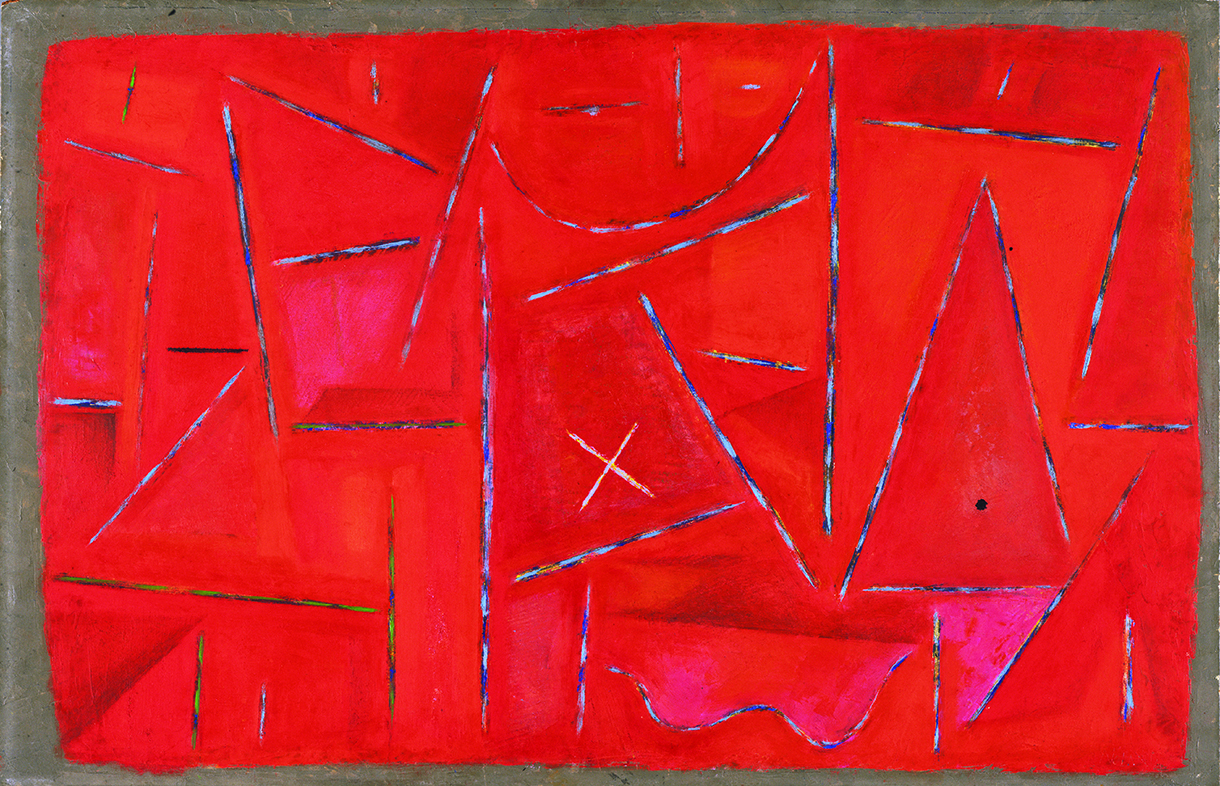

The Phillips Collection, Washington, DC, Acquired 1952 Art © Estate of Kenneth Noland/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY.

In the Garden, 1952. Oil on hardboard, 19 1/2 x 30 inches.

MAKING A NAME

Greenberg curated Noland into a 1954 gallery show; two years later the Museum of Modern Art included him in the traveling exhibition Young American Painters; and in 1957 he had his first solo show at New York’s Tibor de Nagy Gallery. In 1964 Greenberg again boosted Noland’s career, presenting him alongside Louis, Frankenthaler, Ellsworth Kelly, Frank Stella, Jack Bush, and Jules Olitski in Post-Painterly Abstraction, a traveling show organized at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art that helped establish the Color Field movement. Noland and Louis were recognized as leading figures in what would be known as the Washington Color School that also included Gene Davis, Anne Truitt, Sam Gilliam, Alma Thomas, and others.

Noland’s work was soon included in group shows at the Tate Gallery in London, the American pavilion at the 1964 Venice Biennale (along with Louis, Johns, and Robert Rauschenberg, who won the Biennale’s grand prize), as well as the landmark 1969 Metropolitan Museum exhibition New York Painting and Sculpture: 1940–1970. Throughout the 1960s and 1970s he appeared regularly in Whitney Annual and Biennial exhibitions, the Corcoran Biennial of Contemporary American Painting, the Carnegie International, and Documenta. In 1977 the Guggenheim organized a traveling retrospective, and he went on to have one-artist shows in Mexico City; Bilbao, Spain; Houston; Liverpool, England; and Youngstown, Ohio.

CHANGING TASTES

Noland’s heyday was relatively short-lived. By the 1970s interest turned from Abstract Expressionism and color-field painting to Minimalism, Conceptualism, and Pop Art. Though Noland’s reductive images are, like those of Stella, seen today as precursors to Minimalism, some critics considered his works soulless illustrations of Greenberg’s formalist theory. And their popularity among collectors led the same works to be denigrated as empty tokens of good taste. Time magazine in 1965 referred to color-field paintings as “avant-garde tapestries,” and in 1970 the critic Brian O’Doherty called them “the ultimate capitalist art.”

Noland’s mural-sized stripe paintings—some 7 feet tall and 20-odd feet long—were likened to slick products geared to corporate types. Discussing the striped works in his 1972 book Other Criteria, art historian Leo Steinberg referred to them as “principles of efficiency, speed, and machine-tooled precision which, in the imagination to which they appeal, tend to associate themselves with the output ofindustry more than of art.”

Many people still find Noland’s formulations overly simple and somewhat cold, but others appreciate their sleek design and color dynamics or treat them as mandala-like objects for meditative contemplation. Art historian Mollie Berger relates the targets to ideas espoused by psychoanalyst Wilhelm Reich. Noland saw a Reichian therapist from 1950 on, and later said Reich had been the most important influence on his life. Berger explains that Reich believed that organic matter is imbued with an energy called orgone, whose free flow through the body is requisite for physical, mental, and sexual health. Orgone flow could be blocked by “character armor” that individuals create in response to trauma. Berger posits that Noland’s targets—which resemble diagrams in Reich’s books—may symbolize the Reichian practice of self-centering, with the circles representing armor that breaks down in the ragged-edged rings to allow the individual to reconnect with the energy circulating in the world.

Acquired 1960; Art © Estate of Kenneth Noland/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY. Paintings, 1434, American.

Beginning, 1966. Magna on canvas; 90 x 95 7/8 inches.

Gift of the Joseph H. Hirshhorn Foundation, 1966. Photography by Lee Stalsworth. Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden.

April, 1960. Acrylic on canvas; 16 x 16 inches.

AT THE HEART

For all the heady theory underlying his work, the consensus among those who knew him was that Noland was humble and down-to-earth. “His talk was without any pretension, devoid of ‘art speak,’” recalled the British sculptor Anthony Caro, who described his friend as “modest and self-deprecating [with] an infectious sense of humor and fun,” as well as an affection for jazz, especially Charlie Parker and Thelonious Monk. According to one of his assistants, Noland was easygoing in public but driven in the studio. “He really was an artist 12 hours a day, seven days a week, even into his 80s,” he said.

He married four times, the first in 1950 to Cornelia Langer, daughter of a North Dakota Senator and a student of sculptor David Smith. They had three children including Cady Noland, a well-known sculptor and installation artist. Marriages to psychologist Stephanie Gordon and art historian Peggy Schiffer, with whom he had a son, both ended in divorce. In 1994 he married Paige Rense, editor-in-chief of Architectural Digest, with whom he shared his final years.

In 1961 he moved to Manhattan. After his friend Louis’ death in 1962, he purchased a farm from the estate of poet Robert Frost in South Shaftsbury, Vermont. For decades he divided his time between Lower Manhattan and Vermont, where he became close to painter Jules Olitski and British sculptor Anthony Caro, who were teaching at nearby Bennington College. In the 1980s and ’90s he spent much of his time at the farm, using two former dairy barns as a painting studio and workshop for papermaking, an interest in his later decades. He had set up his own shop called Gully Paper in North Hoosick, New York, collaborated with paper makers in Barcelona and Japan, and then brought his equipment to the farm and taught papermaking at Bennington College. In 2002 he and Rense put the farm up for sale, sent the papermaking gear to a Vermont art center, and relocated to the coastal town of Port Clyde, Maine, where he died of kidney cancer in 2010 at the age of 85. The new owners converted the farm into a bed-and-breakfast called Taraden, and returned the papermaking setup to the barn where they operate a workshop.

Late in life, Noland revisited his targets, rendering the circles in softer hues, with more painterly texture and transparency, and on colored backgrounds. He titled the series Mysteries, and perhaps the delicacy and meditative quality betrays a spiritual longing. “I like to think of painting without subject matter as music without words,” he said in 1988. “It affects our innermost being as space, spaces, air.” To the end he believed that abstraction had a future. “It’s a fertile field that we barely have explored,” he said in 1994, “and young artists will return to it. I’m certain.”